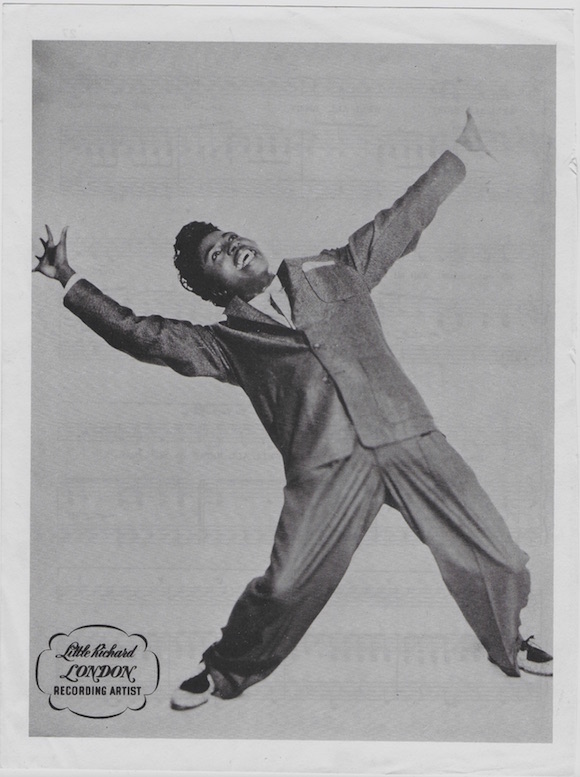

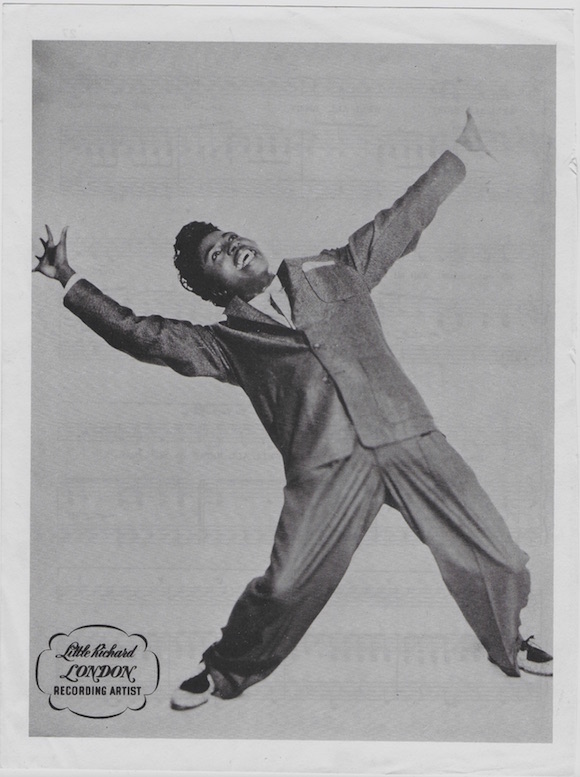

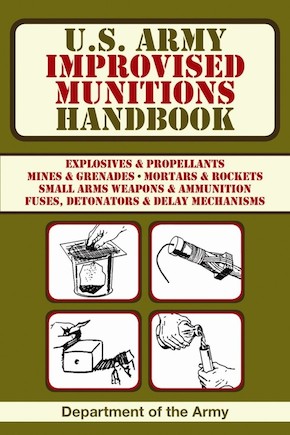

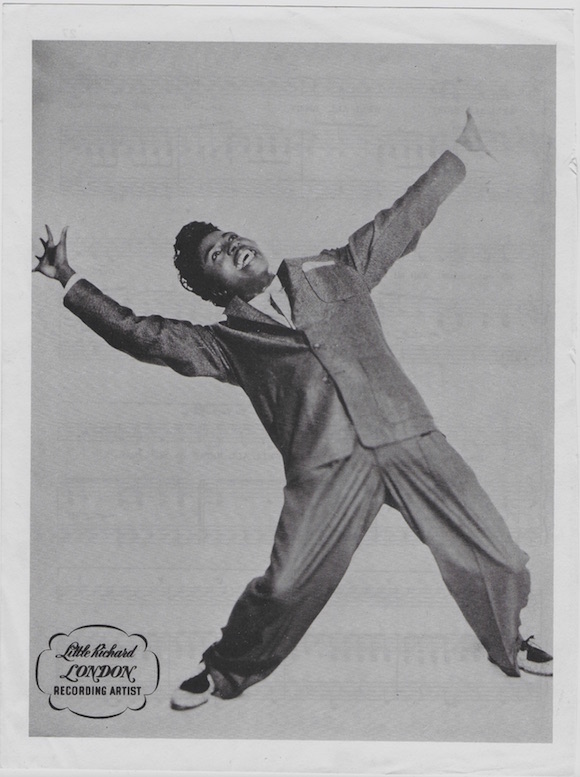

//London Records promotional image, 1958//

In 1956 the Hollywood photographer John E. Reed took a series of promotional shots of the stars of DJ Alan Freed’s rocksploitation flick Don’t Knock The Rock.

//London Records promotional image, 1958//

In 1956 the Hollywood photographer John E. Reed took a series of promotional shots of the stars of DJ Alan Freed’s rocksploitation flick Don’t Knock The Rock.

//Chuck Berry with Paul Shaffer, Thames TV Studios, Lower Ground, Waterloo, London, May 16, 1995//

I saw Chuck Berry play live twice, and have written previously about the first time when, supported by David Bowie-endorsed revivalist rockers Fumble, he performed a truncated set at the Rainbow theatre in north London’s Finsbury Park in September 1973.

The second time was frankly bizarre. He and Little Richard sat in with Paul Shaffer and his band during a live broadcast of The David Letterman Show from the UK capital in 1995.

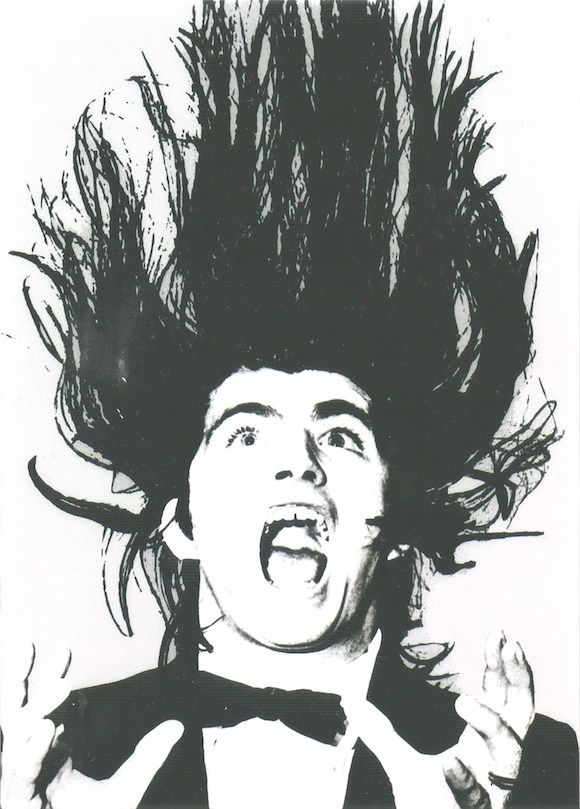

//1964 promotional shot of Screaming Lord Sutch//

//From top left: Chinese Communist Party pamphlet, 1971; McLaren in Let It Rock 1972; Proclamation by Engels and Marx, 1881; Title lettering, Belgian film poster, 1958//

A year or so ago I established the source material for one of the first designs generated by Malcolm McLaren in the fashion partnership he conducted with Vivienne Westwood in the 70s and early 80s.

Now I can reveal the inspiration: text contained in an unprepossessing Communist booklet celebrating the short-lived “Paris Commune” government of 19th Century revolutionary France.

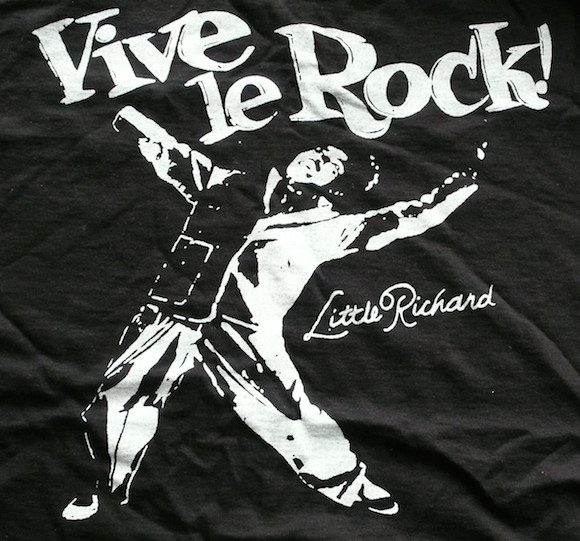

//Front and back of Vive le Rock/Punk Rock Disco and the radical political and military texts used as source material for the design//

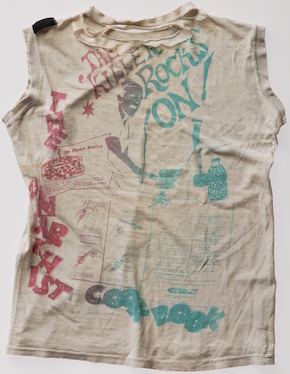

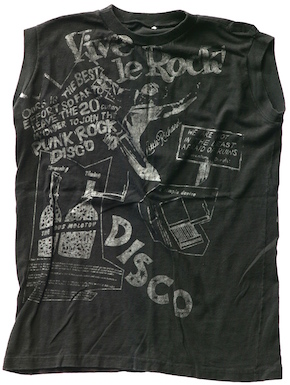

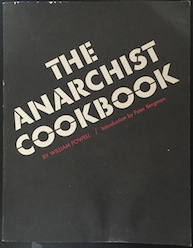

There were T-shirts left over from the Wembley Rock & Roll revival festival in our cupboards in South Clapham; we had to do something with them. Sid Vicious liked them just the way they were and was often photographed in the original Vive Le Rock! design. But I needed to throw a few messages across them and reinvent them. So, I married the slogan and images of Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis with words and drawings from various texts, using the title of The Anarchist Cookbook as well as the famous phrase of the Spanish anarchist Buenaventura Durutti.

Malcolm McLaren 2008

Imogen Hunt is a recent graduate from London College Of Fashion who tells me she was inspired by my work to write her thesis for the college’s history of fashion and culture course.

Part of Hunt’s dissertation – on the importance of the Situationist International and King Mob to the development of punk style – is dedicated to an examination of the influences and source material for the double-sided design Vive Le Rock/Punk Rock Disco, which was printed on the front and back of t-shirts and tops first sold in Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s King’s Road store Seditionaries in 1978.

//Lobby card for High School Confidential!, 1958. This is from the opening scene, where Lewis sings the movie’s title track//

Let It Rock was digging in the ruins of past cultures that you cared about. It was giving them another brief moment in the sun. It wasn’t about doing anything new. It was an homage. It was nostalgia.

Malcolm McLaren to Momus, 2002

Forty three years after its creation I can reveal the source of the Jerry Lee Lewis image which appeared on the Let It Rock t-shirt design “The ‘Killer’ Rocks On!”.

It is from a lobby card for Alan Freed’s 1958 rocksploitation flick High Street Confidential!; an original was just one of the pieces of 50s ephemera adorning Let It Rock’s premises at 430 King’s Road in 1972.

//Malcolm McLaren in front of display of Belgian 50s rock n roll movie posters inside Let It Rock, 430 King’s Road, January 1972. Note Vive le Rock! poster top left. Photo: David Parkinson//

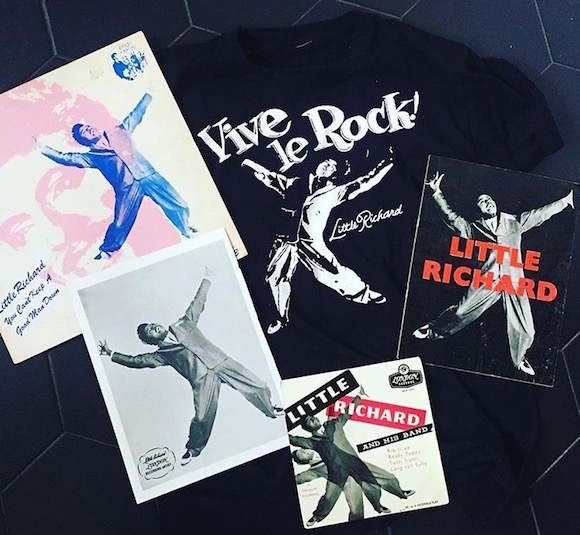

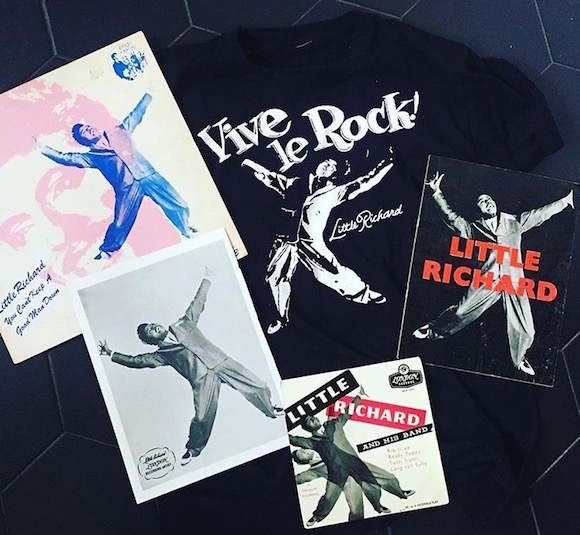

//Taken by John E. Reed in 1956 to promote teen-movie Don’t Knock The Rock, the photo was reissued by London Records to mark the release of the four-track EP Little Richard And His Band//

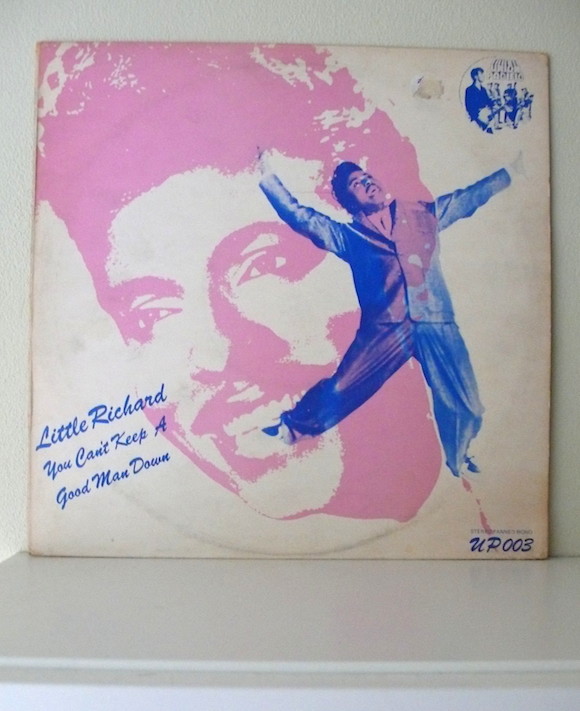

//Front cover, You Can’t Keep A Good Man Down, Little Richard, Union Pacific, 1972. Designer: Unknown//

//As shown on this repro, McLaren’s design for the Little Richard shirt sold at the London Rock N Roll Festival held at Wembley Stadium in August 1972//

Yet another example of Malcolm McLaren’s astounding design talent is examined across a number of exhibits at the Let It Rock show, which opens at Copenhagen’s Bella Center on Sunday (August 3).

In 1972 McLaren expanded his investigations into 50s pop design culture by producing a series of t-shirt designs celebrating the great American rock & roll stars performing on the bill of the one-day festival at London’s Wembley Stadium that August.

McLaren continued to followed the path dictated by his formidable art education by creating new artworks out of the juxtaposition of found objects. A 1956 promotional photograph of Little Richard provided the main image for the shirt dedicated to The Georgia Peach.

In 1972 it also appeared on the cover of the UK compilation You Can’t Keep A Good Man Down; that year also witnessed a revival of interest in the pompadoured Richard Penniman after Let It Rock customer Charles (now Lord) Saatchi featured a Little Richard song in a 50s-styled TV advert for Libro jeans.

McLaren flipped the image, reversed it out and positioned the exuberant figure with the joyous title lettering from a rock & roll movie poster he stocked in Let It Rock. Vive Le Rock! was, in fact, the French title of the 1958 US production Let’s Rock, so tied indirectly with the name McLaren had chosen for his own venture. In Britain the film was marketed under the tamer Keep It Cool.

//McLaren later incorporated the Vive Le Rock! elements into a fresh composite for sale in 430 King’s Road when it was Seditionaries in 1979. This also featured Situationist slogans, a quote from the early 20th century Spanish anarcho-syndicalist Buenaventura Durruti and “recipes” from William Powell’s The Anarchist’s Cookbook, first published in 1971//

The Copenhagen show features a Let It Rock installation complete with a series of large prints of previously unseen photographs taken by David Parkinson inside 430 King’s Road in January 1972. Included is a full version of the image at the top of this post, as well as a Vive le Rock! shirt and the Little Richard LP cover.

Let It Rock: The Look Of Music The Sound Of Fashion is at the Crystal Hall in Copenhagen’s Bella Center from August 3-6.

Read more here.

*This post was revised and updated to reflect fresh information on the source of the image on March 11, 2017*

It is relatively common knowledge among those interested in the careers of Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood and their series of extraordinary shops that they supplied clothes to the 1973 album Golden Hour Of Rock & Roll; Let It Rock at 430 King’s Road was clearly credited on the back of the record sleeve.

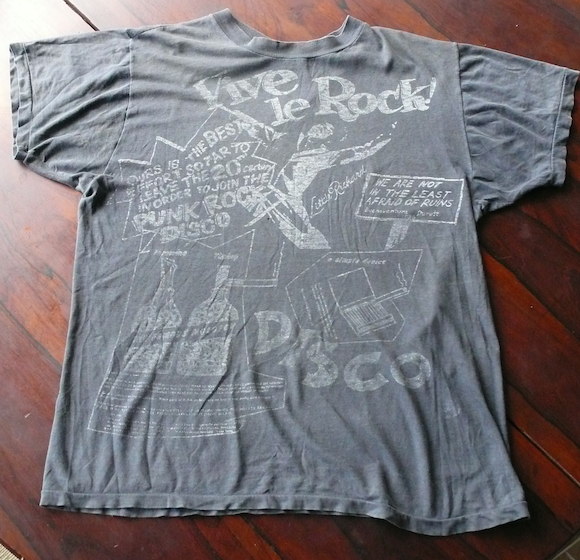

//The photograph on the Rock Archive cover was flipped to better accommodate the text. Here it is as originally shot//

But I have fresh information which helps towards a greater understanding of McLaren’s project to investigate the detritus of popular culture’s recent past. During a bout of research recently I came across this earlier and hitherto undocumented use of Let It Rock clothing in a music context: the front cover of Rock Archive, a budget LP compilation released by the specialist British independent label Windmill in 1972.

And I am detailing the clothes on the cover with images taken inside Let It Rock which have never been previously published.

//Starke shirts with 50s sports jacket on Let It Rock wall, January 1972. Photograph: David Parkinson//

Each garment worn by the model – whose attempts at rocking out resulted in his giving every appearance of suffering considerable pain – comes from the deadstock of British brands assiduously assembled by Malcolm McLaren and his art-school friend Patrick Casey for the opening of the world’s first avowedly post-modern retail outlet in November 1971.

From the ground up, the Rock Archive cover star wore black suede Denson’s Fine Poynts, ice-blue Lybro jeans with 5in cuffs, a Frederick Starke flyaway collar shirt and a studded and decorated Lewis Leathers early 60s Lightning jacket (which featured a highly collectable 6-5 Special patch).

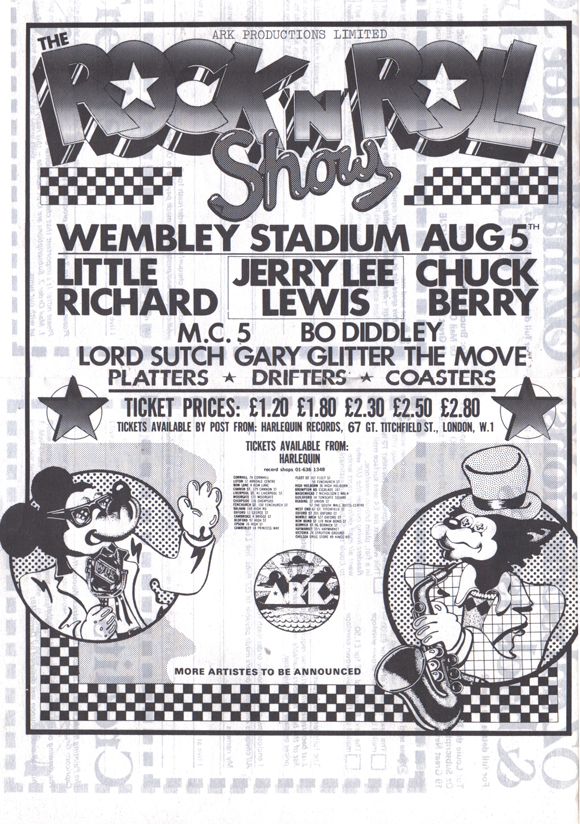

//Flyer for The Rock n Roll Show printed on the back of a subscription form for Oz magazine, July 1972. The Move were replaced by lead member Roy Wood’s new band Wizzard; this was their first gig. Original Brit-rocker Heinz was added to the bill; his backing band would soon become Dr Feelgood//

I acquired my first underground press publications in the summer of 1972, at about the point when the sector was taking the nosedive from which it never recovered.

Still, better late than Sharon Tate, as they say. Aged 12, my taste had been whetted by sneak peeks at an older brother’s collection of magazines when a guy called Kevin O’Keefe who lived down the road gave me a few copies of Oz, including number 43, the July issue.

A few weeks later, to my astonishment, the newsagents in Hendon’s Church Road started stocking Frendz. I folded issue 33 between a couple of music papers and pored over it in my bedroom.

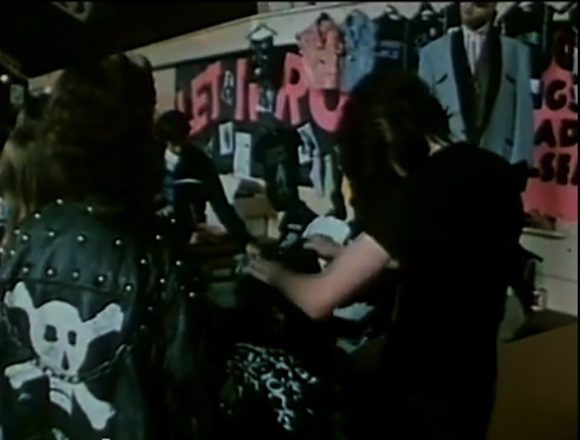

//Crowds around the Let It Rock stand. From the 1973 film London Rock N Roll Show directed by Peter Clifton//

Neither of the magazines are shining examples of the genre, but they had something in common: the centre spread of OZ 43 contained a subscription form back-printed with a flyer for the London Rock N Roll Show, a one-day festival of original 50s acts and those who could claim kinship held at Wembley Stadium on August 5 that year.

And for me the most beguiling article in Frendz 33 was a two-page stream-of-consciousness report of the event filed by one Douglas Gordon and illustrated with photographs by Pennie Smith, soon to leave for the NME and carve out her reputation as one of rock photography’s all-time greats.

Recent Comments