Memories of Mick Farren: An entertaining afternoon in West Hollywood and a champagne-drenched night in Islington

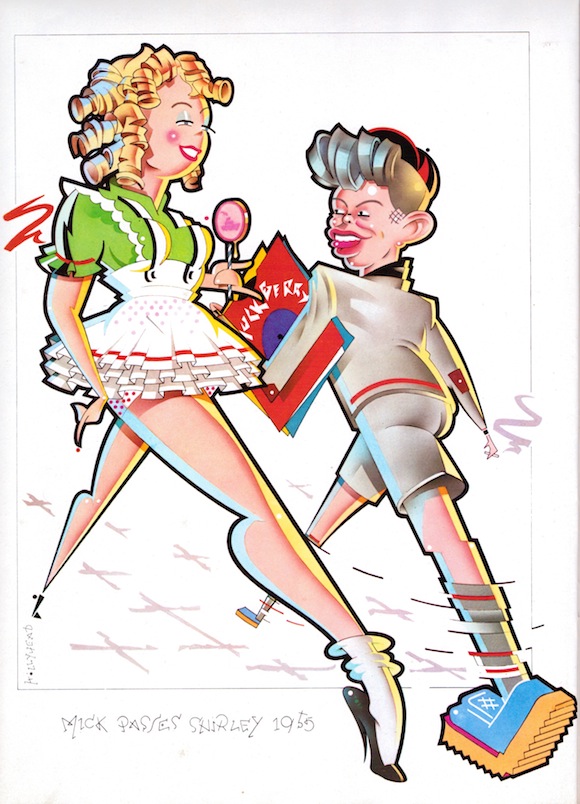

//’Mick Passes Shirley, 1955′ Illustration for a feature about growing up in the 50s by Mick Farren, Club International 1975 by Hollyhead/NTA from an idea of George Hardie’s//

Growing up in London in the 60s and 70s with an interest in the counterculture, music and street politics meant that the shaggy-headed figure of Mick Farren loomed large on the landscape.

I was too young to have experienced at first hand this White Panther, Deviant and all-round Motherfucker’s antics as an agitator of what he described as “the psychedelic left”, when he drew on his deep reserves of fierce intelligence and street-suss to command the door of UFO, the editorial team of International Times, the Phun City festival (which featured the MC5) and also attention from the police (who unsuccessfully brought obscenity charges against Nasty Tales, the comic book he published with his first wife Joy Hebditch, illustrator Edward Barker and IT copy editor Paul Lewis).

Having successfully defended himself and the others, Farren emerged acquitted from the Old Bailey and hit the ground running with a prodigious literary outpouring channeled through every available medium in the wake of the collapse of the underground press: 1972’s youth revolution polemic Watch Out Kids was followed by dystopian novels and non-fiction books, as well as regular journalism for publications from soft-porn magazine Club International to Nick Logan’s New Musical Express, to which he contributed from March 1974.

By then Farren was the mainstay of the Ladbroke Grove crowd whose house bands I adored: Hawkwind (he wrote the lyrics for Lemmy’s song Lost Johnny) and the Pink Fairies (the line-up included former members of The Deviants).

In this period the NME was covering the most interesting aspects of popular culture like no other British publication; there were occasional offerings in the Sunday Times Magazine, Harpers & Queen and even New Society and the New Statesman, but week-in, week-out, NME was the must-read, and Farren was one of the reasons.

He later told me: “The big battle at the NME was: did we put out a kind of high-school magazine about everything which might be interesting to a bunch of people pulled together by their liking for music, or did we put out purely a music magazine?

“I mean, how could we write about Bob Marley without at least giving an insight into colonialism or the politics of Trenchtown?

“My rant, which was repeated all the way down the line, was: ‘Why bother to write about the new ELO album on the day The Godfather II comes out?

“For my first piece I turned in copy about Star Trek and the Trekkie cult and then wrote about Evel Knievel… I was writing about Kenneth Anger and all kinds of shit.”

While Farren’s music journalism is best remembered for his 1976 critique of bloated stadium acts The Titanic Sails At Dawn, it was his Anger piece that summer which spoke to me, igniting a decades-long interest in the director (spookily I was in the audience for Anger’s q&a at the ICA last Sunday; the night before Farren died after collapsing onstage while performing with The Deviants across town at London venue The Borderline).

I brought up the impact of the Anger interview when I interviewed Farren in 2000 for my music press history In Their Own Write. As requested, I arrived at his dimly-lit pad on King’s Road in LA’s West Hollywood with a six-pack of beer and spent an illuminating and entertaining afternoon in his company.

Farren was by turns charming and vitriolic, but also consistently funny, not least when analysing how he squared the regular wages from NME publisher IPC with his revolutionary tendencies.

“I did start writing about music when I discovered record companies, trips to America and free coke,” he admitted. “They were totally unscrupulous, so our attitude was: ‘Yeah, why the fuck not?'”

I last met Farren at Glastonbury two years ago; in pretty poor shape, he sat through most of his performance on the Spirit Of ’71 stage. Afterwards an oxygen mask was clamped to his face, such had been the onset of emphysema.

I prefer to remember Farren in November 2001, when he and I shared a book-reading double-bill at north London venue Filthy McNasty’s; In Their Own Write had just been published and he was launching his memoir Give The Anarchist A Cigarette. It was a memorable evening. Farren’s London countercultural muckers were out in force and the curious attendees included Felix from Basement Jaxx.

Another Felix (Dennis, publishing magnate, Oz Trial defendant and a close friend of Farren’s) had organised a magnum of champagne for Farren’s table at the back of the pub.

I was up first and read excerpts from the chapters concerning the relevant period in the NME’s history. From the get-go a single heckler maintained a rising level of abuse, laced with suppositions about my sexual preferences and a running critique of my sartorial choices for the evening.

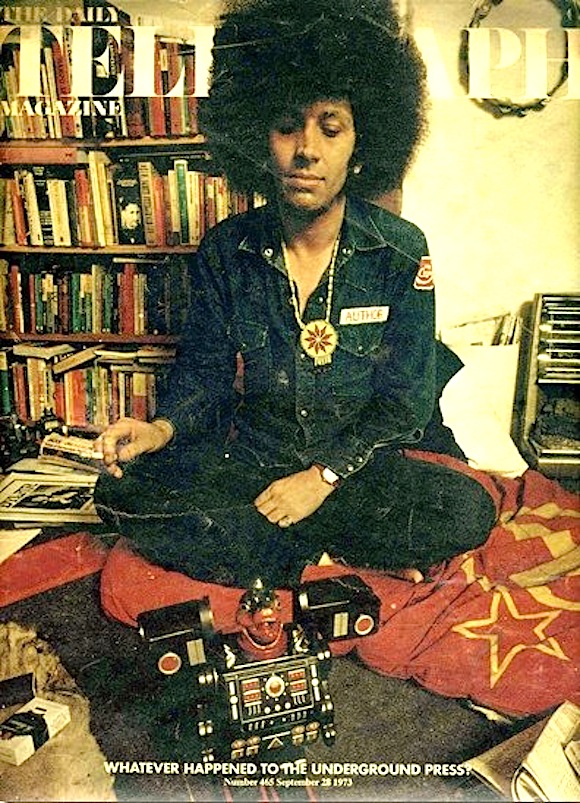

//Farren with (back to camera) Larry Wallis, Filthy McNasty’s, north London, November 2001. Photo: Unknown//

After about five minutes I reproached the individual firmly, peering through the smoke (them were the days) and gloom to identify him. Of course, there was Mick, sat at the back, big-nosed and grinning through his frizzy mop. And the magnum of champagne was empty.

There was nothing else for it. I gave him the floor, to tremendous applause.