Blessed & Blasted: BLAST 1. 06.1914

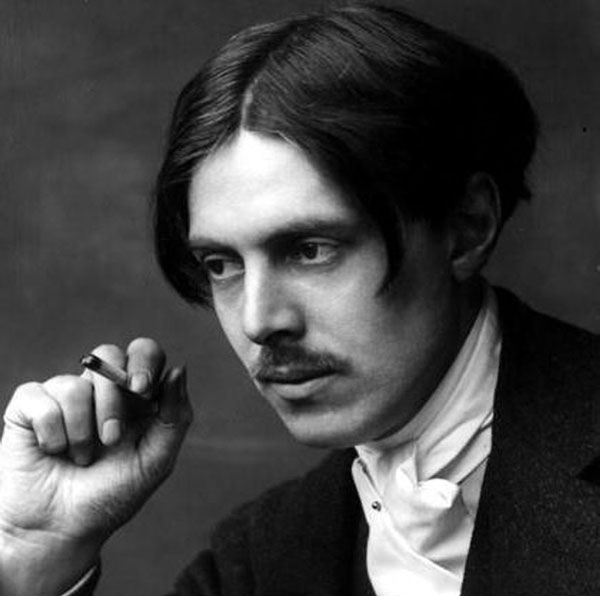

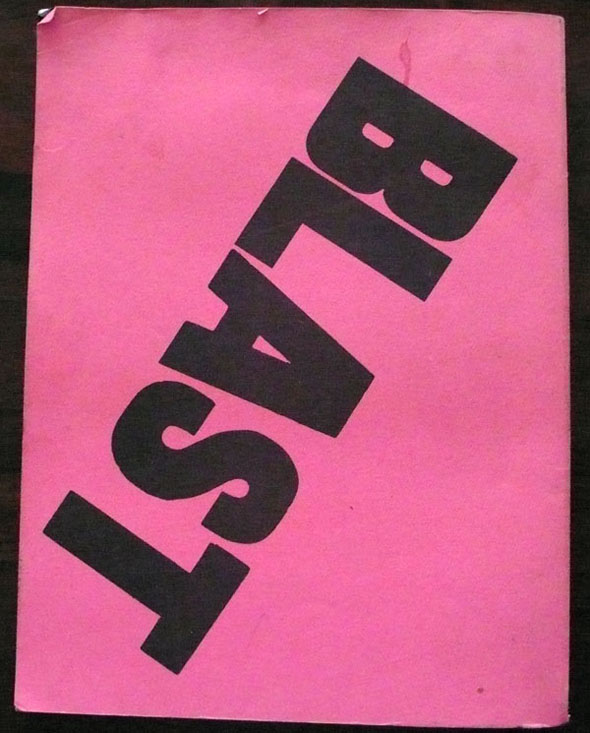

Wyndham Lewis’ 1914 publication Blast 1 is the daddy of the modern aesthetic manifesto.

It’s also a Modernist objet d’art.

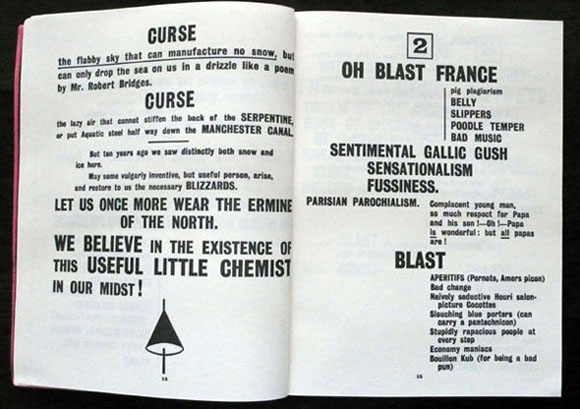

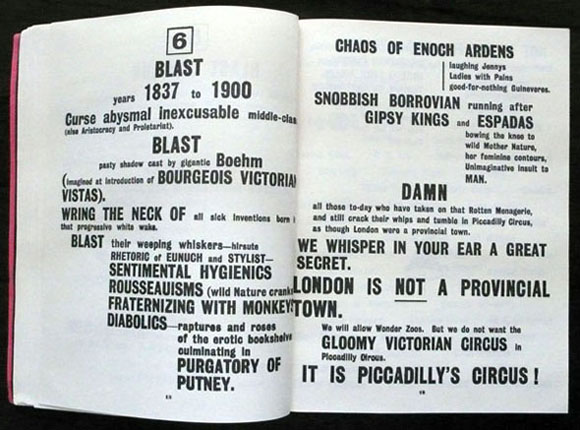

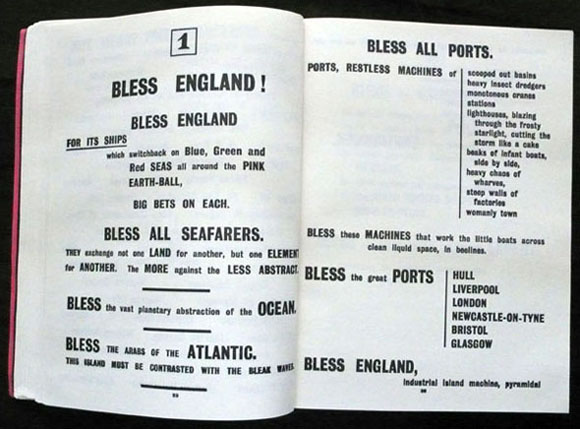

Iconoclastic and satiric, at times inchoate and irrational, Blast’s aim was to establish Vorticism‘s endorsement of the machine age and and simultaneous disavowal of the stultifying Romantic legacy of the Victorian era.

As Bradford Morrow wrote in his 1981 essay Blueprint To The Vortex (which is the foreword to this, the 1989 issue by Black Sparrow Press): “Its intentions were quite simple: to revive English art and literature and shine an electrifying light into murky corners of Georgian passivity.”

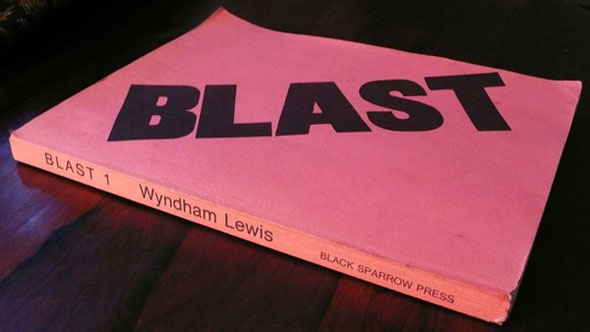

Taking his cue from Filippo Marinetti’s attempt to modernise Italian art and social discourse with the 1909 Futurist Manifesto, the Canadian-born Lewis aimed for maximum impact with the 12″ x 9″ folio format (which gave rise to the name the “puce monster”) and text set in bold san-serif type of varying size.

“With its machine gun typography, commanding dimensions and blinding covers, Blast enacted itself as the physical demonstration of the aesthetic theorems outlined within,” wrote Morrow.

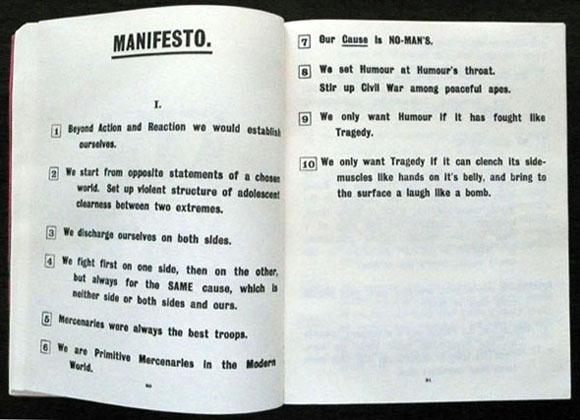

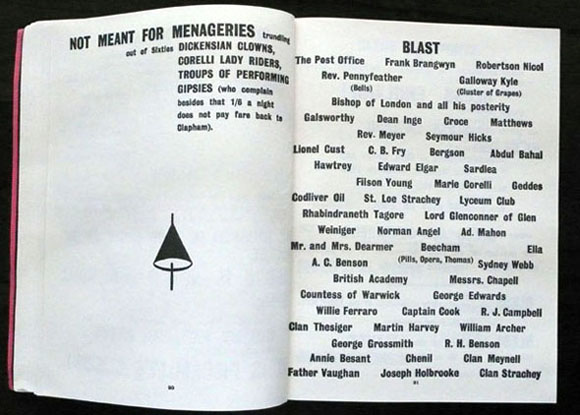

The core of Blast 1 is the manifesto written mainly by Lewis with assistance from Ezra Pound, running to 20 pages with a summary of 10 principles and a list of the “blasted” and “blessed”.

In this way there is a direct correlation to such later tracts as the 1974 pre-punk loves/hates t-shirt dreamed up by Bernie Rhodes with Malcolm McLaren and Gerry Goldstein, You’re Gonna Wake Up One Of These Mornings And Know Which Side Of The Bed You’ve Been Lying On.

Blast 1 also represents a roll-call of practitioners of early 20th Century modernism with fiction from Rebecca West and Ford Madox Ford, poetry by Pound and paintings, drawings and sculpture by Jacob Epstein, Frederick Etchells, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, the recently deceased Frederick Spencer Gore (for whom there was an obit), Cuthbert Hamilton and Edward Wadsworth (who also translated extracts from Wassily Kandinsky’s 1912 book The Art Of Spiritual Harmony).

Blast 1 is packed to the gills: there is a message of amity to the Suffragettes (who are implored to cease attacking art as an element of their campaigning), discussions of Picasso’s latest work, feng shui and futurism and Lewis’ Vorticist play The Enemy Of The Stars.

The critical response to Blast – both negative and positive – was widespread and Lewis delighted in the role of intellectual agitator, dubbing himself “The Enemy”.

Published in July 1915, Blast 2 was naturally preoccupied by WWI; in fact the conflict had already claimed the life of contributor Gaudier-Brzeska. His personal manifesto – which had been sent from the trenches in France – was printed along with a simple obituary.

“The aesthetic explosion which figured into the title of the Vorticists’ journal had proved to be a bitter, prophetic analogue of what was to overshadow all Europe for the next several years,” wrote Morrow.

There was to be no Blast 3; Lewis himself left for the Front in May 1917, returning after the Great War to write and paint, though, like Pound, his initial embracing of Fascism resulted in critical disfavour unto his death in 1957.

Nevertheless his declaration in Blast 2 rings true today: “We are the first men of a Future that has not materialised. We belong to a ‘great age’ that has not ‘come off’. We moved too quickly for the world. We set too sharp a pace.”

The 2009 Thames & Hudson reissue of Blast is available here.