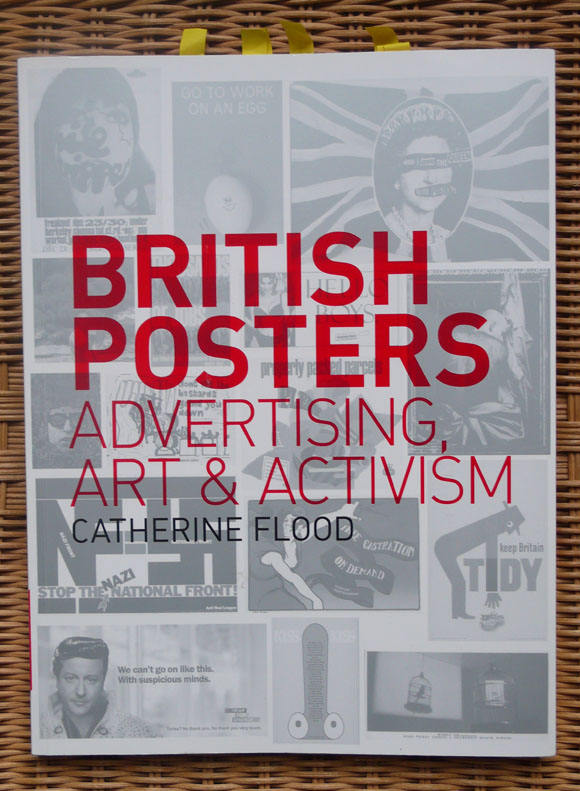

British Posters: Advertising Art & Activism

“People do love huge pieces of paper”.

So runs the quote heading up a section in V&A curator Catherine Flood’s excellent overview British Posters: Advertising Art & Activism, published by the museum to coincide with its multifarious design celebrations this Olympic year.

And it’s true. We do.

Or we all did, when this vital form was simultaneously a mass-medium and a highly personal communications device, when huge promotional budgets and lack of urban controls resulted in the accretive papering of our street-scapes. Meanwhile, behind closed doors, we gave posters pride of place on the walls of our bedrooms, bedsits and sitting rooms.

//Top left: Your Britain, Fight For It Now, Abram Games, 1942. Right: Keep Death Off The Road, Carelessness Kills, William Little, 1949.//

These days, only some of us continue our romance with large pieces of paper. If we’re designers or design fans, says Flood in her conclusion, we are likely to speak like-unto-like via self-published projects. Or if we’re connected to particular areas of life – pop, politics, fashion, film, sport, art, advertising, photography – then the poster evokes places and spaces from the past like no other vehicle.

Serendipitously, the preparation of the book coincided with the uncovering of a wall of posters from the late 50s during refurbishment of Notting Hill tube station in west London. Writes Flood: “Like a datable layer of archaeology, they offer a glimpse of the city at a particular moment and place – evidence of what Londoners in 1959 saw and were prompted to think about as they went about their daily journeys. By directing our gaze and imagination, posters help define our visual experience of urban space.”

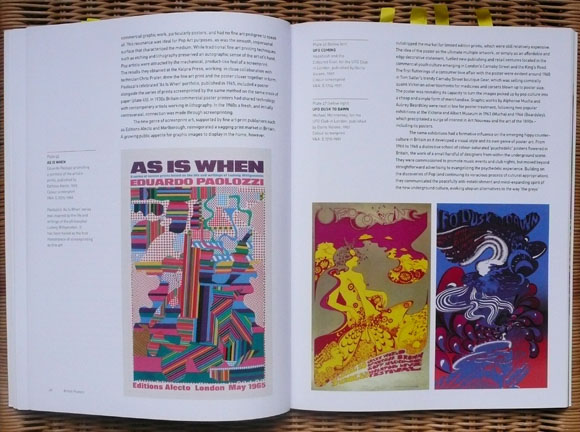

//Bottom left: As Is When, Eduardo Paolozzi, 1965 ("hailed as the first masterpiece of screenprinting as fine art"). Right: UFO Coming, Hapshash And The Coloured Coat + UFO Dusk To Dawn, Mike McInnerney, both 1967.//

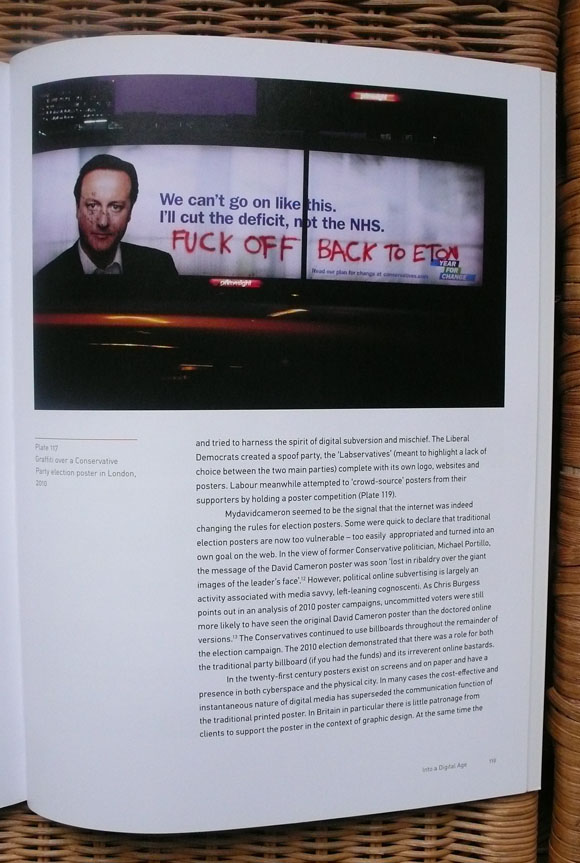

Citing design authority Rick Poynor’s belief that “the intense visual pleasures offered by graphic culture are beginning to usurp the place of fine art”, Flood’s book tracks the often binary potency of the poster in the baby-boom age.

We see how the reconstructive messages of the austerity years gave way to the confidence expressed not just by the slick group practices of the 60s but also the artists and wide-eyed psychedelic warriors of that era. Corralled by agit-propsters and sophisticated ad-men alike in the 70s and 80s, thereafter the mass use of, and interest in, the physical form declined as attentions turned to cyberspace.

If there is one quibble, it is that there are no dimensions given for the works portrayed in the book; scale is an important factor in this medium (one thinks of Barney Bubbles’ 60in x 40in Ian Dury Loves You poster featured here and currently dominating the ‘punk’ section of the V&A’s British Design show).

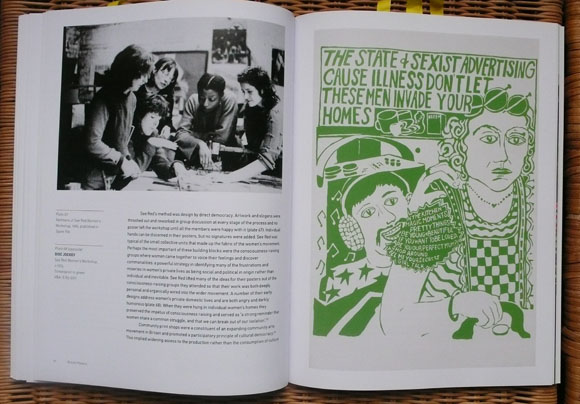

//Top left: Members of See Red Women's Workshop, 1980. Right: Disc Jockey, See Red Women's Workshop c. 1974.//

//Top Left: There Is Only One Loony Left... John Morris, 1987. Right: New Labour, New Danger, M&C Saatchi, 1997.//

Keen to avoid a requiem, Flood’s view is that the very materiality of graphic wall art has ensured increased significance over recent years. In this way contemporary British letterpress studios such as Typoretum, the Society Of Revisionist Typographers and the transplanted Carteles la Candelaria are upholding the virtues of “hands-on immediacy and inky alchemy” in the digital age.

British Posters: Advertising Art & Activism by Catherine Flood is available here.