When Charlie met Malcolm

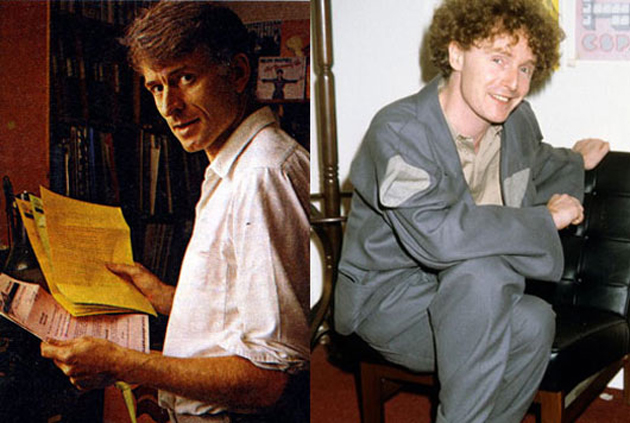

//Gillett + McLaren, 1983.//

Year-ends and beginnings naturally bring a sense of loss, of time passed and experiences weighed.

For me, 2010 will always mark the deaths of two individuals of personal import and also of lasting significance to our culture: Charlie Gillett and Malcolm McLaren.

These apparently disparate individuals – Gillett 68 and McLaren 64 at their time of passing on, respectively, March 17 and April 8 – shared several characteristics, not least idiosyncratic and uncompromising viewpoints and an abiding interest in bringing vanguard music into the mainstream.

Charlie was among folk and popular music’s most prominent enthusiasts – though he never liked the phrase, it is his achievement that “world music” entered western lives – and, as art consultant Bernd Wurlitzer wrote in 2008: “Malcolm McLaren is and has been an artist in the purest sense of the word for his entire adult life.”

Malcolm has been dismissed as a person for whom music was merely to be used; this was not so. He was passionate and knowledgeable on the subject, as this recording underlines – it’s a broadcast of Charlie’s Thursday evening show Radio Jukebox from January 1983.

Charlie Gillett, Covent Garden, London, July 2009. Photo: Neil McKenzie Matthews.

Malcolm McLaren, Factory Studios, Brooklyn, NY, October 2009. Photo: Eva Tuerbl.

Malcolm was promoting Duck Rock and chose 10 tracks of great variety and substance. It’s not included, but there is a song which first connected the two for me.

I heard Charlie Feathers’ rockabilly stunner One Hand Loose blaring forth from 430 King’s Road at just about the time that Charlie was plucking it from obscurity on his historic Honky Tonk show (on Radio London).

On my first and last encounters with both, music was on the agenda. In 1975 I talked with Malcolm, believe it or not, about Jimi Hendrix. The last time I saw him, in November 2009 in Newcastle, he turned me onto Les Chats Sauvages.

That same month I encountered Charlie, also for the last time. We considered the ill-health which had precluded Flaco Jiminez from joining Nick Lowe and Ry Cooder on their live dates that summer (for the record Charlie believed the replacement should have been Geraint Watkins).

And the first time I met him, in 1979 or 1980, Charlie urged me to buy a Wynonie Harris compilation in a local record shop.

There were many more similarities than differences between the two erudite, educated personalities: these were both forthright, restless spirits, unwilling and unable to time-serve or tread water.

They also shared certainty, with sturdily framed critiques providing unique and often authoritative insights.

On a mundane level there was another connection: they both resided in inner south London suburb Clapham for significant phases of their lives, which is where I come in, having lived here for the majority of the last thirty years.

Strange to say, since he traveled restlessly and was by no means a close friend, I felt I knew Malcolm better than Charlie, who I bumped into regularly since he lived around the corner, in the house bought in the 60s in what was then an undesirable area.

On the occasion when Charlie persuaded me to purchase the Wynonie Harris record, I gushed about the release of Johnnie Allan’s Promised Land on his pioneering independent label Oval.

By this time Charlie was famous. Sound Of The City – cannily transcribed from his degree thesis – and work on magazines Cream and Let It Rock helped define mature British music journalism.

Honky Tonk provided the soundtrack for the UK’s early- to mid-70s drive to authenticity and roots music (opening the doors along the way for the likes of Elvis Costello, Ian Dury, Graham Parker and Dire Straits as well as one-offs such as Lene Lovich) and he had also managed Dury’s delightfully odd Kilburn & The High Roads (whose anarchic yet razor-sharp street theatre provided formative inspiration for the Sex Pistols).

And again, like Malcolm, Charlie was a champion of black dance music, in his case when it was consigned to the specialist pages of the music press. Charlie’s reviews for the unfashionable Record Mirror were required reading for anybody with an interest in funk, soul and what would become disco.

Charlie was not a person associated with visual style (which might explain why he exited a performance of The Exploding Plastic Inevitable at Manhattan’s The Dom in 1966), yet his was a distinctive presence. There are those who remember the herringbone raglan overcoat he wore into the Noughties from his days managing the Kilburns, and latterly his look was captured by That’s Not My Age.

Unlike Malcolm, Charlie was an active sports participant, and so it was I encountered him playing football on Clapham Common on Thursday evenings and Sunday mornings.

In the late 80s I recommended to him the music of a Gambian kora player I knew. In the letter I have kept, Charlie charmingly pointed out that the poor chap simply wasn’t up to snuff. I had been blinded by the exoticism of what I heard. Charlie gauged its originality and true worth.

When I freelanced at Music Week in the 90s we met at record company receptions and I conjoined him to a few music quizzes: in 1997 our team won that put on by Mojo magazine.

I interviewed Charlie for In Their Own Write, where his observations cut through the clutter of the oral history format. Asked at the launch party at the Brit Art gallery in Shoreditch (this was 2001) for his thoughts on the book, Charlie’s blunt response was that a narrative would have been preferable: “I wanted to hear what you thought.”

He was, of course, right. It is my intention to rewrite, revise and update ITOW; the prospect that Charlie will have his way more than a decade later is gladdening.

The book which preceded it, The Look, brought me back into contact with Malcolm, who I had encountered occasionally at openings and events, and again when I worked for a film magazine in Los Angeles and he was trying his hand at movie production. For NME in the early 90s I covered his plan to realise a biopic of Led Zeppelin’s manager Peter Grant.

In 1994 as an organizer of a London art auction for the charity War Child I ensured he was invited. We chatted and I posed him for a photograph with David Bailey and Marie Helvin before he engaged in a bidding competition and won the brace of paintings by Shane MacGowan.

Five years later a mutual acquaintance, the music entrepreneur Alan McGee, invested in testing the viability of Malcolm’s candidacy for the role of Lord Mayor Of London.

Joining Malcolm on the hustings at the London School of Economics was fun; after a fine performance, the pair of us were the only customers of the crowded student bar wearing suits and ties, and, tellingly, struggled to obtain anything approaching sophisticated refreshment. Having struck out with requests from Bloody Marys and Campari & Sodas, we settled for bottled water. “Blimey,” he muttered. “Guess that’ll teach me to order such 60s drinks.”

Malcolm contributed much information as well as the foreword to The Look, though he was more interested in discussing a planned musical on the life of Christian Dior, Jack Kerouac’s stylistic influence over James Dean, London’s beatnik coffee bar scene, the pre-Beatles 60s, anything rather than having to rehash punk.

When I set to work on the second edition in the mid-Noughties, 8-bit/chip-music and China had become new preoccupations, though there was by now a determination to set the record straight in regard to the clothing and shop designs he created between 1971 and 1983 in tandem with Vivienne Westwood.

This was in part sparked by the staging of the revisionist Westwood retrospective a couple of years previously, but was also a reaction to the dumbed-down and mediated interest in this era, as exemplified by the still-unstaunched flood of fake SEX and Seditionaries clothing doing the rounds.

He was right to be fearful that he would be defined by the casual stereotypes of punk, which, after all, was done and dusted within a space of 32 months in what was a spectacular five decades in fashion, art and music.

Once, almost as an aside, I asked Malcolm if he recalled a coffee bar at the underground station Hendon Central in north-west London, just around the corner from his childhood home in the late 50s and early 60s.

I’m from Hendon and this “froffy coffee” joint has a place in my family’s folklore; an older brother of Malcolm’s age had frequented it.

“Malcolm still dreams about that place!” declared his partner Young Kim.

Malcolm nodded, his expression serious, his mouth set firm. “It was another world,” he sighed. “I had such a miserable time at home I’d escape and watch the beatnik girls with their black mascara-ed eyes, dreaming of becoming an art student…”

When I asked him why he had become so passionate about the market in fake punk clothing, he said flatly: “I know now I have to reclaim my story, come to terms with my history.”

This was a couple of years before his death. I believe that Malcolm achieved his goal, and in doing so, his later work was among his best. With the chimerical film pieces Shallow 1-21 and Paris: City Of The XXIst Century, this misunderstood figure emerged as a pure artist, one who no longer found it necessary to manipulate design, clothing, people or, in fact, culture. At the time of his all-too-sudden demise, he was embarked on multifarious projects, many of them art-based.

There is no doubt Malcolm was flawed – which of us isn’t? – and his avowedly anti-sentimental streak was sometimes expressed as cruelty; there are those who nurse the wounds of association with this mercurial character. There are many, many more, like me, whose lives were enriched directly or indirectly.

Of course, Charlie was also not without faults. In Memoirs Of A Geezer, Jah Wobble upset the applecart by describing Charlie as “an energy vampire” in his attitude to business dealings. The subject’s response was to use the moniker to sign off an email congratulating the author on his book.

Above all Malcolm shared with Charlie the quality which characterises people of true creative mettle: generosity of spirit.

Four weeks before he died I received an email from Malcolm on a subject we had been chewing over: “Any more thoughts? Don’t hesitate to pass them by me.”

Would that I could.

Instead I shall enjoy again this broadcast by these two great Londoners. As a child of the capital, I can attest that their radical and inclusive ideas contributed immeasurably to the transformation of the multi-layered visual, social and musical identities of this city.

Delighting in each other’s company, the breadth and quality of the music is matched by the exhilarating charge of their exchanges as Charlie and Malcolm take in such gems as Marie Lloyd’s The Coster Girl In Paris and Pink Floyd’s See Emily Play (Malcolm describes Syd Barrett as one of England’s “great storytellers, along with Charles Dickens and the Sex Pistols. I love him dearly”).

And, at one stage, Malcolm makes the calls live on Buffalo Girls to a field recording made with Trevor Horn in West Virginia.

Only a person of Malcolm’s singularity could sign off with a last-minute wish for a rendition of Haywire Mac’s Hallelujah I’m A Bum, and only a broadcaster of Charlie’s qualities could have accommodated it with such warmth and style.

Hallelujah to both of them.

Malcolm McLaren’s music choices on Charlie Gillett’s Radio Jukebox, Capital Radio, 1983.

1. Take This Hammer – Leadbelly (1942)

2. I’m Not A Juvenile Delinquent – Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers (1957)

3. God Save The Queen – Sex Pistols (1977)

4. World’s Famous Supreme Team/Zulus On A Time Bomb [excerpt] (1983)

5. I’d Like To Live In Paris All The Time (The Coster Girl In Paris) – Marie Lloyd (1912)

6. See Emily Play – The Pink Floyd (1967)

7. Buffalo Girls – The Hilltoppers with Malcolm McLaren (1983)

8. La Siognoria Vostra Sorriso from Madame Butterfly – Giacomo Puccini (1949)

9. Soweto – Malcolm McLaren (1983)

10. Hallelujah I’m A Bum – Harry “Haywire Mac” McLintock (1928)

Thanks to Michael at bootsalesounds.com for making this recording available, That’s Not My Age for the photograph of Charlie and Eva Tuerbl for her photograph of Malcolm.