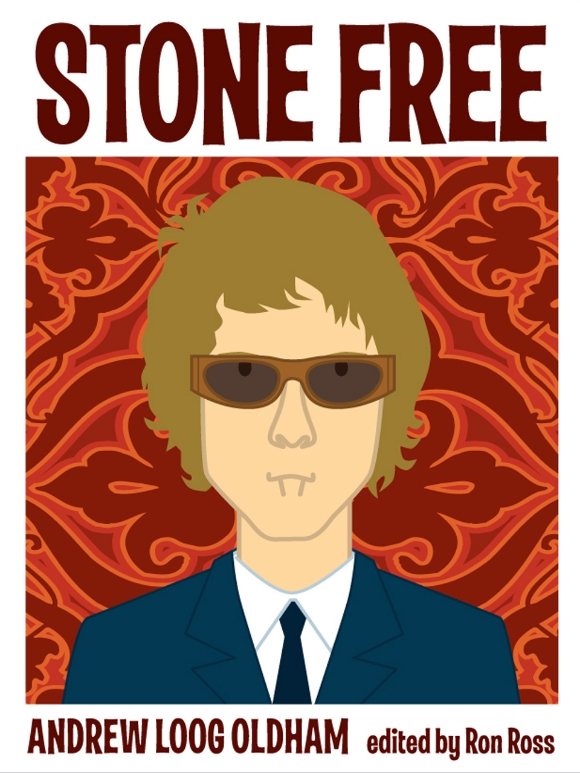

Previously unpublished: Rejected book review of Stone Free by Andrew Loog Oldham

A couple of months back I was commissioned to review Andrew Loog Oldham’s latest book Stone Free for a website, but my copy was rejected on the basis of my use of “criticism”; they prefer to keep things – in their words – “upbeat”.

I like the commissioner, think the site is good and had no problem with the rejection, but thought it may be of interest, so here it is:

“I have little use for the past and do not give it much thought.”

Now that is rich.

One anticipates and has often applauded bare-faced sauce from the music business maverick turned self-chronicler Andrew Loog Oldham, author of Stoned (384 densely-packed pages of reflection on life from birth in 1944 to the point of managing the Rolling Stones in 1963, with “drug-cuts” into the 70s and 80s), 2Stoned (480 pages on his four-year stewardship of same) and a “fictionalised biography” of Abba (on which we need not dwell).

When this confession – even if it is soon qualified – arrives 10 chapters and 140 pages in to Oldham’s new digital-only tome Stone Free, it produces a whoop not of glee but of derision.

Loog old boy, for yonks now you have been threshing through the experiences of the first half of your life and the wealth of knowledge accumulated. Very often (see the 50s music biz detailing of Stoned), amid the score-settling and catty bon mots, you have delivered unto our arid cultural present rare insights into that brief and picked-to-death period of the late 20th Century when the untamed entertainment industry was the wellspring for social forces beyond commerce.

The past is all that concerns Stone Free, with its conceit of a hustler’s guide to 10 of popular music’s – yuck – “pimpresarios”, from convicted murderer Phil Spector and tax evader Allen Klein to charm-free Don Arden and predatory Larry Parnes.

Also stitched in are quirkily-drawn sketches of his “first role model”, Oldham’s mother’s sugar daddy, a north London investment banker named Alec Morris, and Ballet Russe founder Sergei Diaghilev.

By dedicating a chapter to each, with an anti-celebration of the Stones’ 50th anniversary and a tour around the duplicity-filled history of the catalogue of his Immediate Records, Oldham strays into the territory mapped out a quarter of a century ago by Johnny Rogan’s superb Svengalis & Starmakers.

That book – which similarly covered Arden, Parnes et al – presented Rogan the poised professional, coolly spearing and dissecting his subjects. Here, by contrast, Oldham is the enthusiastic semi-amateur scribe, gushy, apparently lightly edited, sentimental even, out to shock by protesting fondness for the likes of Arden, who, post-Savile, would deservedly be spending spells behind bars for excessive mental and physical cruelty, let alone his criminally fiscal stewardship of the careers of such performers as The Small Faces.

For the most part, this matters not. Objectivity and context are swept aside as Oldham plays up access: a visit to Spector in the LA courtroom a couple of days before the bizarre producer was sentenced for the ugly, pointless killing of Lana Clarkson (women, Sharon Osbourne aside, are not served well herein) and a Broadway viewing of the disastrous Klein-produced Edward Albee play The Man Who Had Three Arms (“a temper tantrum in two acts” according to the New York Times’ Frank Rich) make for richly-drawn tableaux.

Oldham is less sound when stepping outside the comfort zone of personal acquaintance and inside knowledge.

A peroration on the career of the late Malcolm McLaren is hamstrung by the fact that their paths never crossed. This should not be an obstacle for so acute an observer, but nevertheless Oldham’s homage takes on the air of a fancifully-phrased Wiki entry by counting down biographical details without illumination beyond occasional speculation that the younger McLaren may have seen the Stones perform live before him (on, we are reminded regularly, April 28, 1963).

In fact McLaren did witness an early Stones performance. He told me this took place at a small venue off Leicester Square and the band left a mark on the impressionable 17-year-old not just because of the vitality on offer; their white shirts, apparently, were defiantly grubby.

This sparks a more pertinent consideration: Oldham – as his career demonstrates (best forget the woeful Street Rats LP, produced for Humble Pie in the mid-70s) and as displayed elsewhere here – is generationally incapable of assimilating the importance of the punk upheaval and its social and cultural aftershocks.

An illustration is the overlong discussion of the mid-70s attempt by manager Adrian Millar to place his pretty boy power pop band The Babys with a major record label.

Given the chemical miasma in which Oldham operated at this time, it is perhaps forgivable that he is under the impression The Babys failed to take in Britain because the music industry here was “too engrossed in all things punk”. This is not so. In reality it was because The Babys (who formed in pre-punk 1975 and via various Kings Road music biz connections were in the audience for a very early Sex Pistols performance, by the way) were No Bloody Good.

Like the dog returns to its vomit, so Oldham is drawn time and again to the Stones. If praise for Keith Richards’ monumentally ungenerous memoir Life strays into hack cover-line territory (“brilliant, salty and searing”), snarking at Jagger is levelled at the camp pitch set by Stoned (in which Oldham wrote that he and the singer were “as close as two boys could be”).

As the collective realisation dawns that the potency of popular music and mass culture is spent, never likely to be regained in the Western world, it’s reassuring to be entertained once more by the memories of one who played his part.

And we are grateful that even if Oldham continues to exercise economy over the actualité – “I do not give much thought to the past” indeed! – he serves to entertain by maintaining his evocations of the phase in our recent history when all was, temporarily at least, shook up.

Stone Free is published by Escargot Books and available to buy here.