John Stephen: Progenitor of a custom-built design movement

“One day, ‘Carnaby Street’ could rank with ‘Bauhaus’ as a descriptive phrase for a design style and design legend.”

Ken and Kate Baynes, Design, August 1966.

Today is the seventh anniversary of Westminster Council’s dedication of a plaque in Carnaby Street to the late fashion retailer John Stephen, the 60s media darling dubbed “The £1m Mod” for his entrepreneurial success and flamboyant lifestyle (houses in Cannes and Milan, a white Alsatian named Prince who dined with him at his regular table at Mirabelle).

Westminster set out to mark Stephen’s “contribution to male fashion”, yet his activities didn’t just propel the 60s boutique explosion. Since the publication of the first edition of my book The Look in 2001 (which included the last interview with Stephen; he died three years later) it has become accepted that Stephen pulled off the considerable coup of introducing informality and ambivalence into the British menswear tradition by drawing on the sartorial aspects of the gay subculture from which he emerged.

And the Stephen effect percolated outwards; as early as 1966 he was identified as one of the key catalysts in the adoption of fresh approaches to design outside of fashion and into packaging, interiors and graphics.

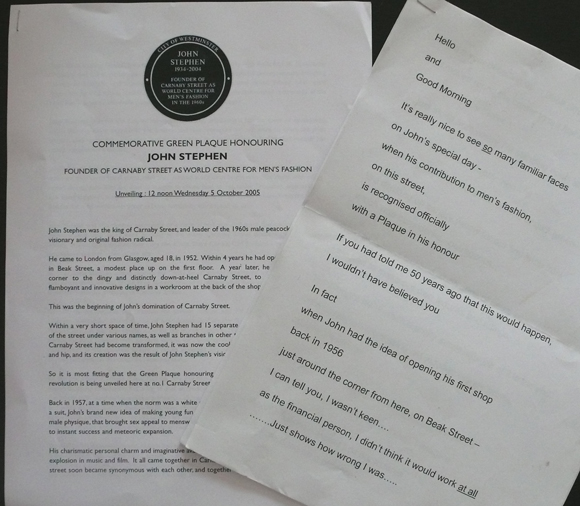

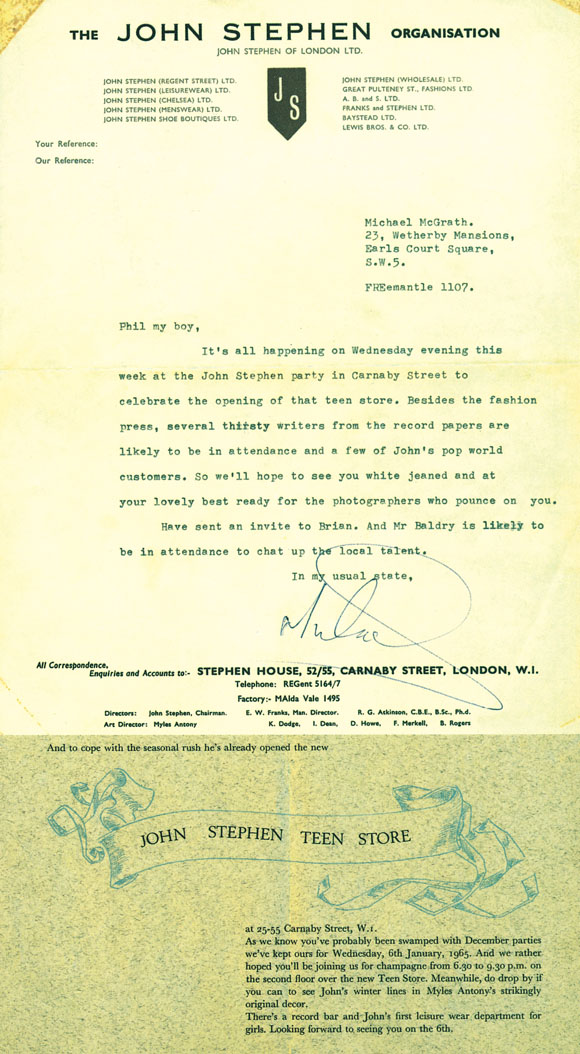

At the plaque unveiling on October 5 2005, a crowd of 100 or so gathered to hear tribute paid by Stephen’s partner of 50 years, Bill Franks. They started business together in Soho’s Beak Street in 1957 and moved around the corner to 5 Carnaby Street a year later.

Franks told the gathering (which included Stephen’s sister and such Carnaby luminaries as Gear’s Tom Salter and I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet’s John Paul) about the make-do-and-mend approach of this post-austerity period:

“We’d blown our tiny budget on cans of canary yellow paint for the front so we made our own fixtures using wooden orange boxes covered in red felt. We could only afford to have one of a style on show, in the most popular size. There was a little room at the back where we’d knock up the order as we took it.

“We also did a bit of wholesaling; our business vehicle was a Vespa, with Mandy the poodle in the basket, John driving and me on the pillion holding the trouser stock.

“One day John bought a thin mohair rug.

“I said: ‘What the hell are you going to do with that?’

“‘Make sweaters,’ said John. Blow me down, the very next day Cliff Richard bought one. That’s how the next fashion was invented.”

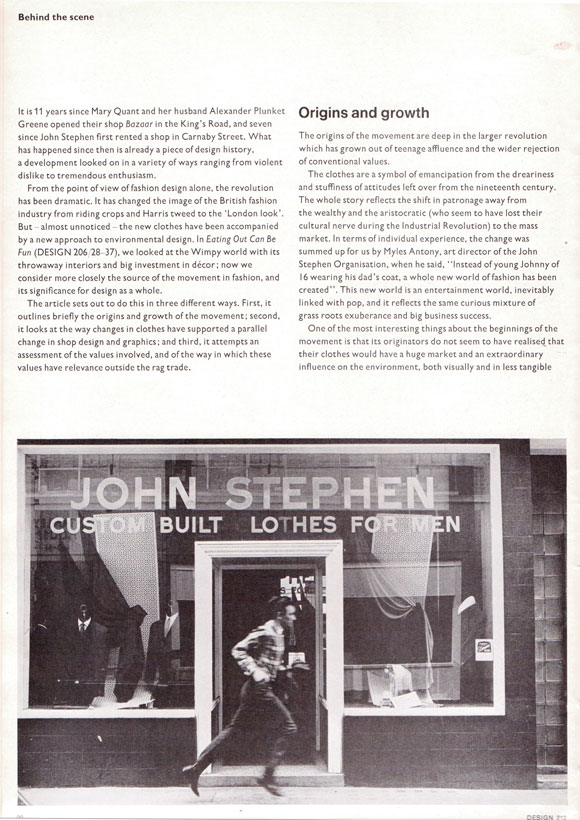

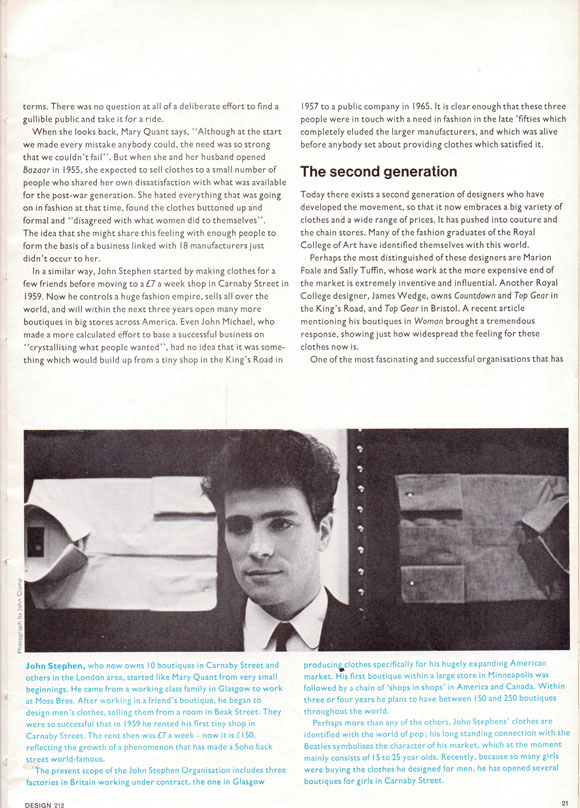

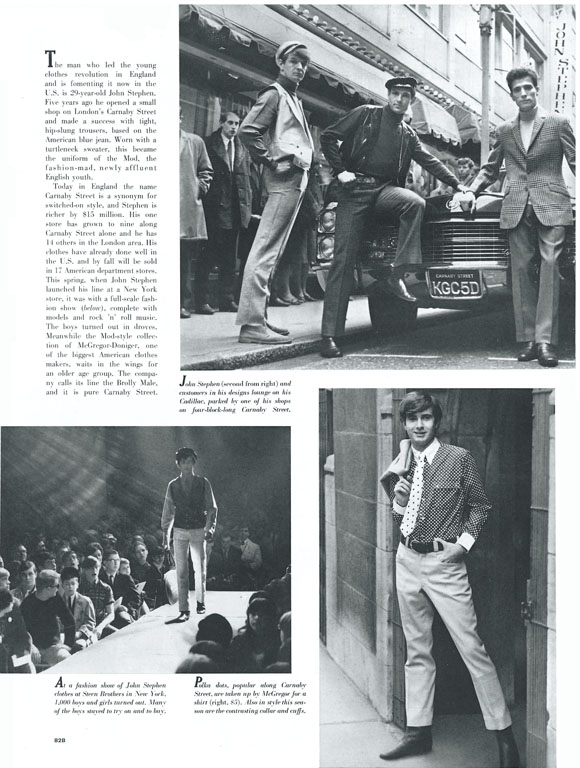

By the time of Behind The Scene, Ken and Kate Baynes’ 1966 Design overview of the Carnaby effect on contemporary visual culture, the 32-year-old Glaswegian and Franks were operating 15 outlets alone in the thoroughfare, with three factories around Britain and canny licensing deals in North America.

//Life May 13, 1966, p82: Stephen (top right) with Cadillac and models; left, showing at Stern Brothers, NYC; lower right, Carnaby-style polka dot shirt by McGregor. Photography: Henry Grossman, Terence Spencer, Ernest Satow.//

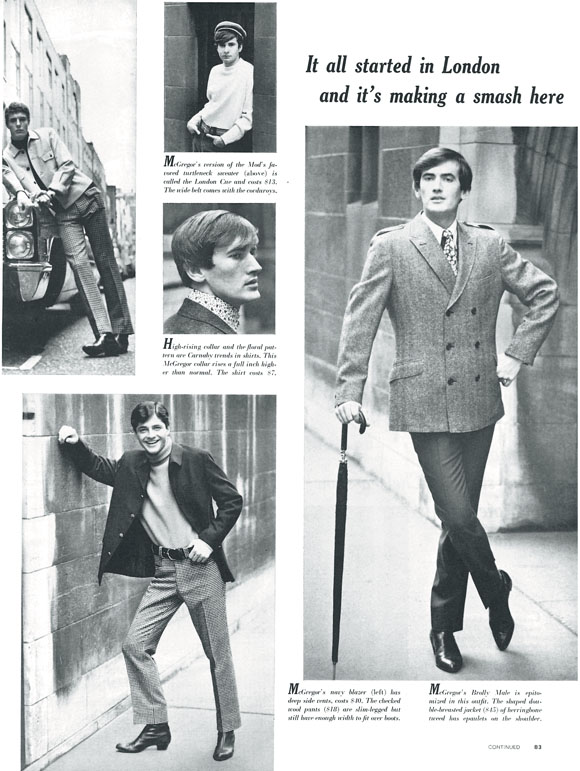

//Life May 13, 1966, p83: Carnaby goes trans-Atlantic - turtleneck, "high-rising" collar shirt, check wool hipsters, cords with wide belt and double-breasted jacket with epaulettes in herringbone, all McGregor. Photography: Henry Grossman, Terence Spencer, Ernest Satow//

//"Phil my boy..." Store opening invite to singer Phil May from John Stephen Organisation art director Myles Anthony. From Unrepentant, The Pretty Things, Fragile/Vital, 1995.//

Stephen, meanwhile, was hailed as the progenitor of a new design movement.

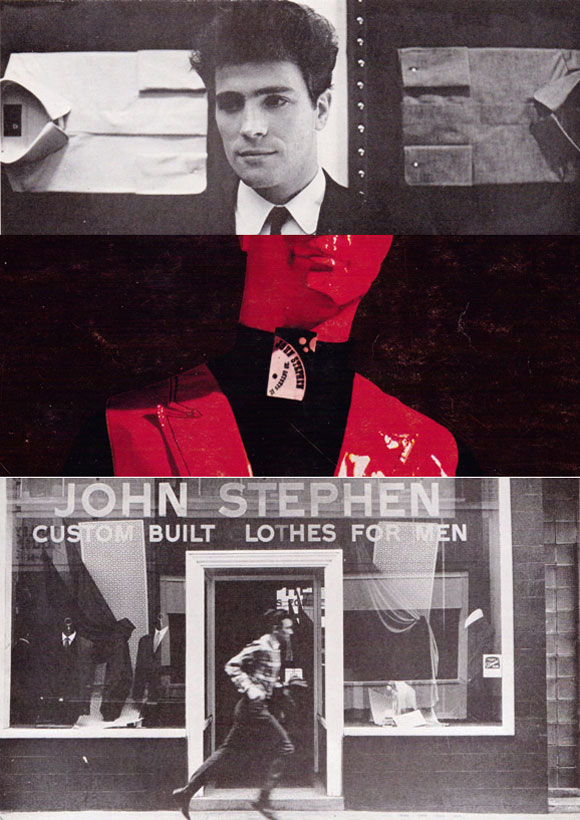

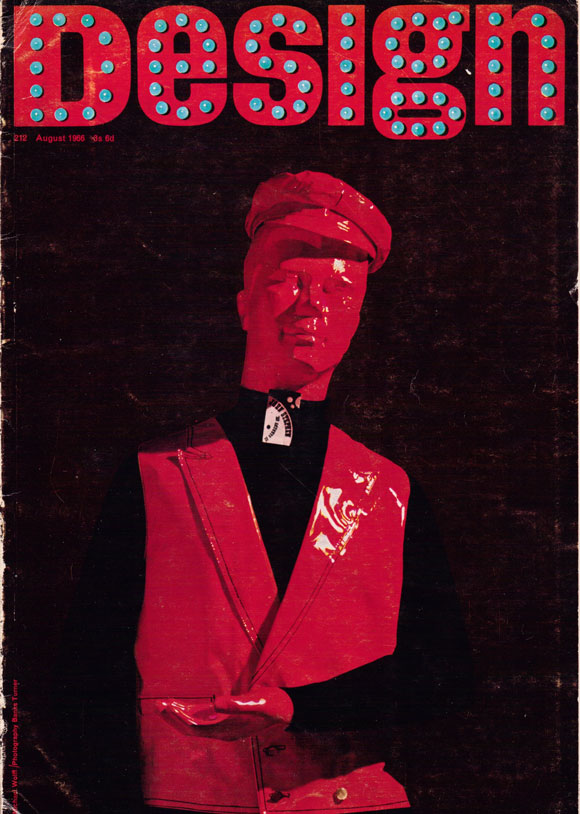

//Stephen clothes on the cover of Design, August 1966. Art direction: Michael Wolff. Photography: Banks Turner.//

Aligning Carnaby’s development with the mid-60s British fast-food boom as exemplified by the “throwaway designs and big investment in decor” at such chains as Wimpy and Golden Egg, the Baynes presented the work of such young graphic, interiors and product designers as Stephen’s art director Myles Anthony, David Cripps (for Foale and Tuffin), Anthony Little (Biba) and Maureen Roffey and Tom Wolsey (Mary Quant).

“Just as the Bauhuas has come to stand for a moment in the history of design when the nineteenth century assumptions were shaken by a new attitude which was part aesthetic, part social, so today the revolution in attitude to things like obsolescence and decoration goes with economic and social changes,” wrote the Baynes. “The Carnaby Street approach which started with clothes is now spilling over into other areas, and what has happened is of great significance for design as a whole.”

It so happens that 1966 stands as the pinnacle not just of the Carnaby phenomenon but also Stephen’s powers; that year in west London operators such as Michael Rainey at Hung On You and Nigel Waymouth at Granny Takes A Trip were stealing the march by reworking the independent fashion retail outlet as art installation and proto-hippie/peacock dandy playpen.

Yet the doorway to their ventures was opened by Stephen. And, as conveyed by Frank’s mohair rug story, Stephen’s achievements in this area are all the more remarkable when it is understood that he operated on a bravura combination of gut instinct and sheer nous.

“I was young and able to plug into what people wanted,” he told me in 2000. “I was the same age and into pop music, so I gave kids something they could wear to complement that. There was nobody else around who was doing it, so I had it all to myself for a long time. Once others started coming through, all they could do was copy me.”