27 acknowledgements: Vivienne Westwood, Ian Kelly + Picador’s defence collapses as they accept The Look as a primary source for the designer’s 2014 biography

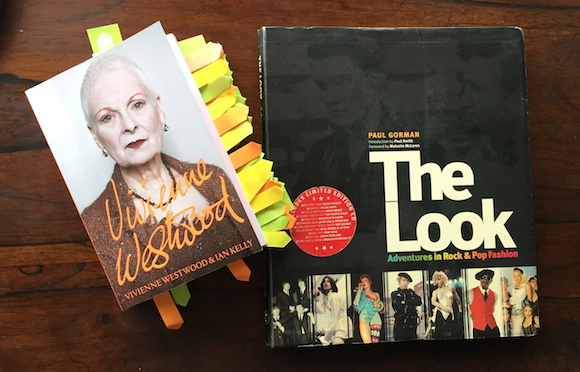

There has been a breakthrough in my challenge to Dame Vivienne Westwood, her co-author Ian Kelly and publisher Picador over their lifting of substantial amounts of material from my book The Look: Adventures In Rock & Pop Fashion for the designer’s 2014 “authorised biography”.

The paperback edition of Vivienne Westwood published last week contains a whopping 27 acknowledgements citing me and The Look.

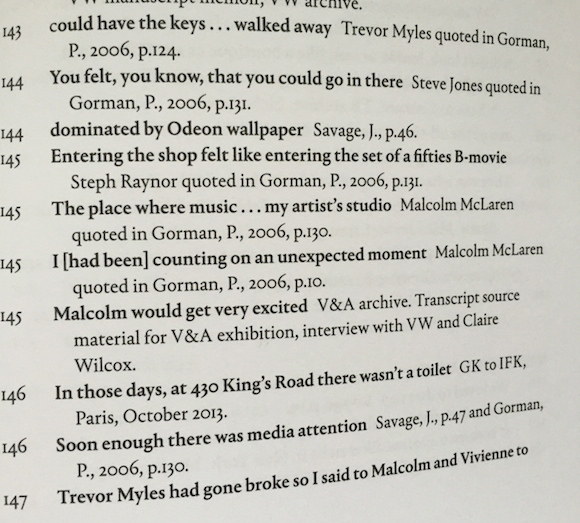

The original edition contained just eight citations to The Look; one referred to material which wasn’t mine and another six were misleadingly given wrong page numbers.

I resorted to legal action on the basis that actually more than 40 passages were taken from The Look, and am advised that these represent a substantial copyright infringement.

Lawyers representing Westwood, Kelly and Picador have been rejecting my claim on the basis that my material came from the designer herself or was in the public domain, so not exclusive to me (even though I have tapes, manuscripts, notes and letters from sources confirming that much of it was granted to me for The Look and also in many cases had never appeared anywhere else).

In effect Westwood, Kelly and Picador’s attitude has been one of “see you in court”.

Up until now.

The publication of the paperback marks the buckling of their defence; it seems the designer, her co-author and the publisher have been advised that to hold their position in a new edition of the book would have been untenable. Certainly the corrected text and dozens of credits to me represent a retreat from their previously bullish stance.

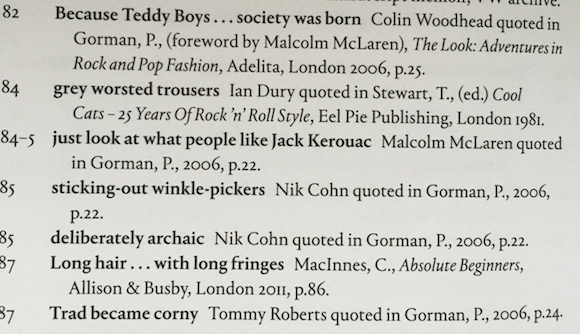

//Note: The source of the Ian Dury quote on p84 was not acknowledged in the first edition. I included this quote in The Look (and credited it to Tony Stewart’s book Cool Cats), so charged the authors and Picador with having lifted it from me. Here, in the paperback version, the source is instead cited as Cool Cats, also now hastily added to the bibliography//

Still, they have wriggled out of credits to me where they can. For example, the paperback has added a citation to Tony Stewart’s 1981 book Cool Cats as a way of avoiding my claim that The Look was the primary source of the Ian Dury quote on page 84 (since I had originally cited it in the context of Teddy Boy style). And curiously, Cool Cats has now been added to the bibliography. One irony is that my letter of claim pointed out to their lawyers that the quote in fact came originally from Stewart’s book. You can bet your bottom dollar that neither Westwood nor Kelly had even heard of the book before I mentioned it but hey presto! Here it is in the new bibliography.

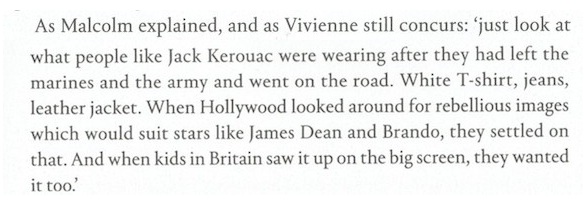

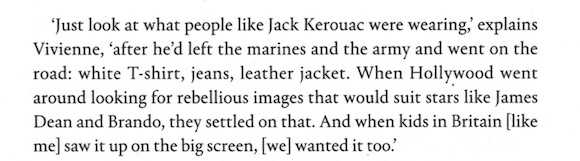

//2014 hardback edition: McLaren’s quote – as spoken to me during a 1999 interview – is attributed verbatim to Westwood//

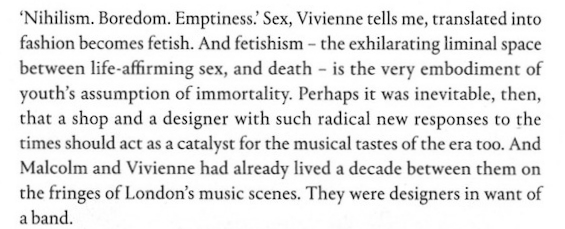

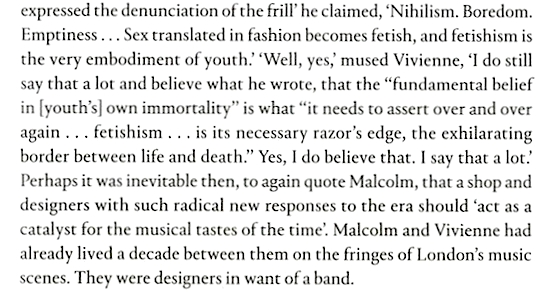

Amusingly, there is much tortuous phrasing and retrospective justification in the paperback, not least in regard to the paragraphs in the hardback which were attributed to Westwood in interviews with Kelly but were in fact word-for-word renditions of text written by Malcolm McLaren for his introduction to The Look or spoken to me in recorded exchanges as far back as 1999.

//2014 hardback: The text derives from McLaren’s introduction to The Look yet Kelly wrote that Westwood had spoken the words to him//

//2015 paperback: The quotes are now attributed to McLaren in another rewrite. The Look is also now credited as the source in the acknowledgements//

In fact, the book emerges in paperback as a prime example of the publishing maxim that you can’t polish a turd.

The multiple obfuscations and inaccuracies continue in the paperback edition, which also contains passages where attempts to correct wrong information have resulted in compounding of the original errors.

As to the impact of the book’s editorial sloppiness on others, it should be noted that one of the serious libels contained in the hardback has been removed in the paperback. Picador – and in particular publisher Paul Baggaley and editor Kris Doyle – can count themselves lucky that the victim chose not to take them to the cleaners.

It is heartening to note that there is redress for some of the others whose copyrights were also filched in the hardback; these are the photographers whose work was wrongfully claimed as belonging to Westwood’s archives.

So the paperback now credits David Parkinson, Barry Plummer, David Dagley and Alain Dister (whose portrait of McLaren and Westwood from 1973 remains cropped to exclude the designer’s late partner). Parties acting for all of these made representations to Picador.

But there are several more images belonging to others who didn’t, and their ownership is still claimed by Westwood, including an exterior of Sex at 430 King’s Road taken by Bob Gruen in 1976 (wrongly dated to 1974 on p137), Westwood and others outside Let It Rock taken by Masayoshi Sukita in 1972 (also wrongly dated – to 1971 – on p122) and Norma Moriceau’s 1977 portrait of Westwood (p182).

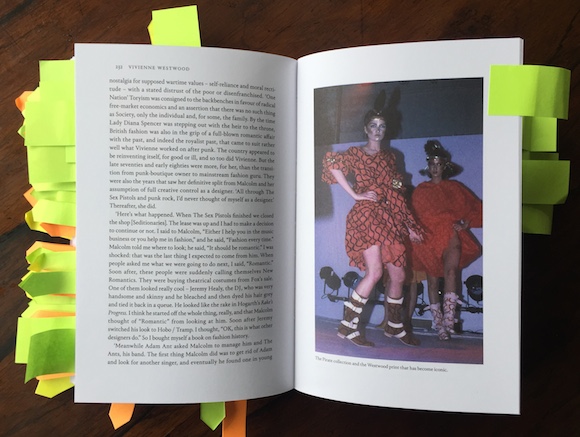

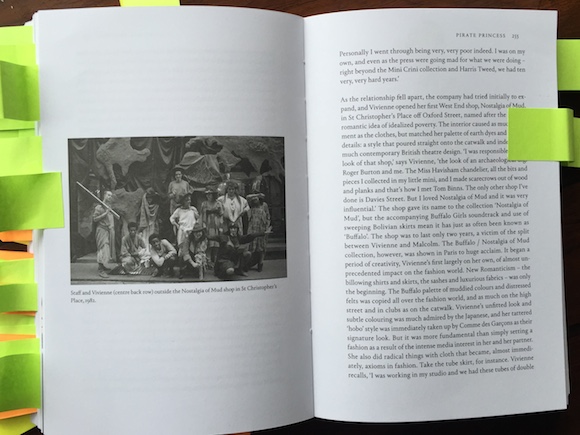

//Robyn Beeche’s photo from the 1982 Nostalgia Of Mud show. Still credited: “Courtesy Vivienne Westwood Archive”//

//Robyn Beeche’s photo of Westwood, Gene Krell, Yvonne Gold and others outside Nostalgia Of Mud 1982. Still credited: “Courtesy Vivienne Westwood Archive”//

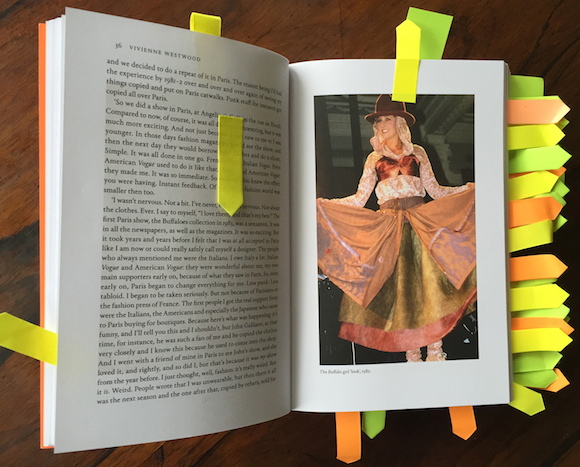

And then there are the photographs taken by Robyn Beeche at the early 80s Westwood and McLaren catwalk shows (pp37, 233) and well as their shop Nostalgia Of Mud (p254) and for the Pirate show invite (p230).

Beeche, who died just a few weeks ago on August 13, is not credited for any of them; instead they are claimed by the Vivienne Westwood Archive.

Robyn was a gentle, spiritual person who almost single-handedly documented Westwood’s rise as a fashion force in the early 80s. It seems incredible that, given this second chance in the paperback, the designer, her publisher and her co-author did not choose to recognise this fact (it was pointed out last year here).

Shame on them.

While I am pleased that acknowledgement of the usage of my work without consent, or recognition has begun, I am keeping my options open, not least since I am out of pocket to the tune of several thousands of pounds in legal costs. In fact, it seems to me that this turn of events bolsters my case.

And the fact remains that Westwood’s important contribution to visual culture has been seriously undermined by this confused and utterly unreliable bio.

One thing: the experience has guaranteed an even-handed approach to my biography of McLaren, which is out in 2017. I will not fall into the trap of partiality which evidently (and unprofessionally) engulfed Kelly and will do my utmost to ensure an accurate and balanced account of the extraordinary partnership Westwood conducted with the late cultural iconoclast.