Die Kunst ist in Gefahr – Blessed & Blasted is back! Art Is In Danger, 1925

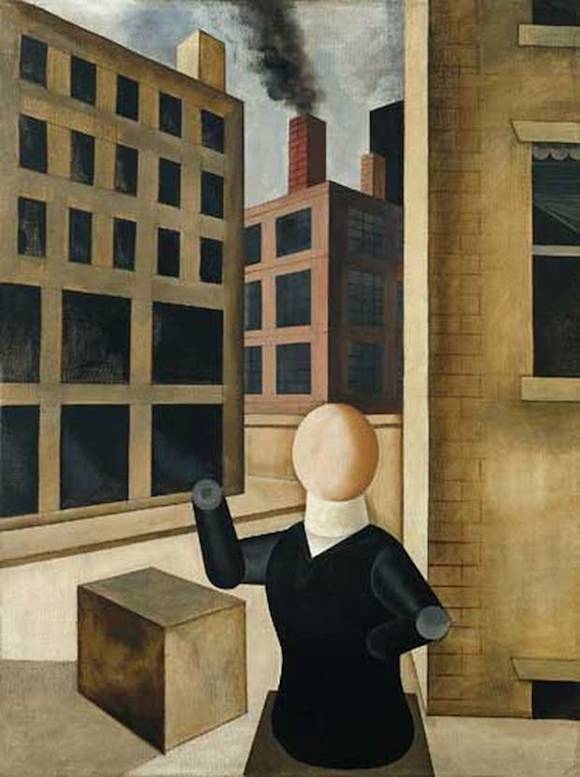

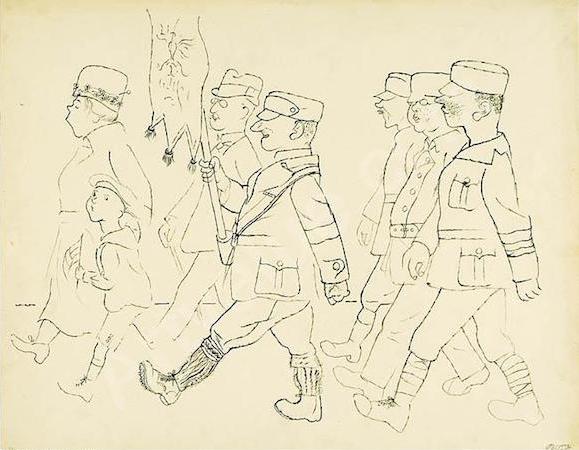

//George Grosz’s book jacket for of Die Kunst is in Gefahr, published by Malik Verlag, Berlin, 1925//

“Today’s artist, if he does not want to run down and become an antiquated dud, has the choice between technology and class warfare propaganda. In both cases he must give up ‘pure art’.

Either he enrolls as an architect, engineer or advertising artist in the army (unfortunately very feudalistically organized) which develops industrial powers and exploits the world; or as a reporter and critic reflecting the face of our times.”

From Last Round, the conclusion to Art Is In Danger

Today I’m returning to Blessed & Blasted – my occasional series about art manifestos – with Art Is In Danger, issued as a small book in 1925 by George Grosz and John Heartfield’s brother Wieland Hertzfelde.

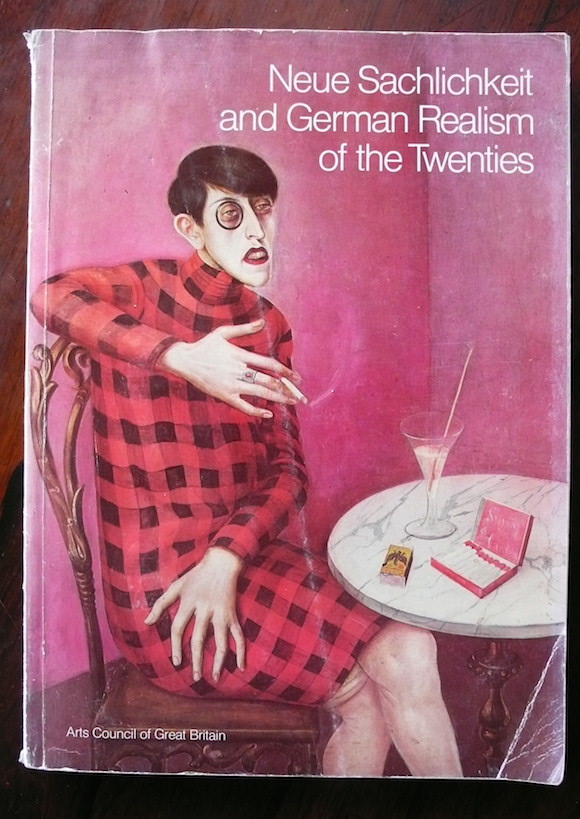

This choice has been triggered by a charity shop acquisition of the catalogue for the 1979 London exhibition Neue Schachlichkeit And German Realism Of The Twenties, an examination of the so-called “New Objectivity” which arose as a reaction to the establishment of Weimar Germany.

As a major proponent, the show naturally featured Grosz’s work alongside that of other such artists as Max Beckmann, Otto Dix and Frank Radziwill and photographers Heartfeld, Karl Blossfeldt and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy.

//Otto Dix’s 1926 Portrait Of The Journalist Sylvia von Harden on the cover of the catalogue for the 1979 show at London’s Hayward Gallery//

Grosz was the dominant force in producing Art Is In Danger, which is described as “the clearest and most effective statement of Grosz’s views” by Dr Wieland Schmied in the Hayward show catalogue.

The manifesto arrived in the wake of the Dada movement’s post WWI assault on artistic traditions, a “reaction to the head-in-the-clouds tendency of so-called holy art, whose disciples brooded over cubes and Gothic art while the generals were painting in blood”.

Grosz’s provocations of the 20s were well represented at the Hayward show, with 20 pieces – including the four reproduced here – confirming his status as the most pitiless caricaturist of the German bourgeoisie, the Weimar Republic and the nation’s militarism.

The much-castigated Grosz was one of the first to publicly rail against the dangers of Nazism and left for American exile in 1933, as Neue Schachlichkeit was brought to a premature end by Hitler’s cultural purges.

Four years after his departure, Grosz’s work was among the 650 exhibits plundered by the Nazis from museums and private collections and put on public display in Munich under the banner of “Degenerate Art”.

In the US Grosz rejected the work of his past and embraced convention. As a consequence his art was never to regain its verve, as Dr Schmied essays in the 1979 catalogue:

“He had suffered at the hands of German nationalism, but could not and would not acknowledge the existence of an American variety, any more than he could see the pettiness and philistinism that lay beneath the surface of Middle America.

He believed himself to be in a consumer paradise, an illicit idyll of technological perfection: the concrete desert became his garden, his Gartenlaube [a bower or summer house].

He now wanted to live only for art, for pure art – and from that moment his art was dead.”

In 1959, Grosz returned to Germany, where he died within a few months of his arrival at the age of 62. Battles rage to this day over ownership of many works by Grosz, which were among those stolen by the Nazis in WWII and are currently held by major collections.

There is a pdf summarising Art Is In Danger on US art historian Maria Elena Buszeck’s blog.

See 21 book covers by Grosz – including that for Die Kunst ist in Gefahr – at 50watts.com here.

You can pick up copies of the Hayward show catalogue here.