Trouble at the Met: Status of half of the punk collection downgraded but dubious designs continue to toxify Costume Institute collection

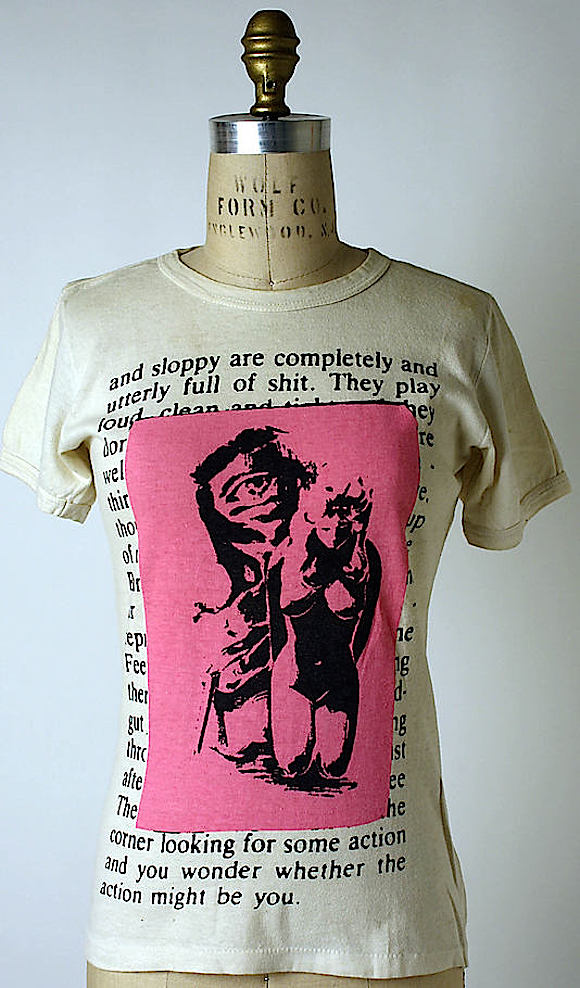

//Dubious. Photo removed from the Met’s website but this T-shirt – like dozens more questionable garments – remains listed in the Costume Institute collection. The listing has been changed to “Attributed to” McLaren & Westwood; previously it was described as an authentic and original example of one of their designs//

A cop-out?

Or another step towards cleaning house at one of the most prestigious fashion collections in the world?

Only time will tell but the reclassification of the status of more than 30 highly collectable and expensive punk garments in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute collection signals a decline in confidence in the authenticity of a great deal of clothing which until recently was proudly proclaimed as original examples of the 70s designs of the late Malcolm McLaren and Dame Vivienne Westwood.

Effectively the museum has downgraded its crucial assurance of provenance for the clothes, which represent around half of the McLaren & Westwood punk fashions in the Met archive; for years they were officially recorded as original, authenticated designs but now Met staff have inserted the phrase “attributed to” into dozens of listings in the collection and on its website.

This follows removal of photography of disputed items from the website along with recommendations to start debugging the collection by deleting offending clothing by “de-accessioning” (the process by which a work is removed from the Met’s collection for sale or disposal*).

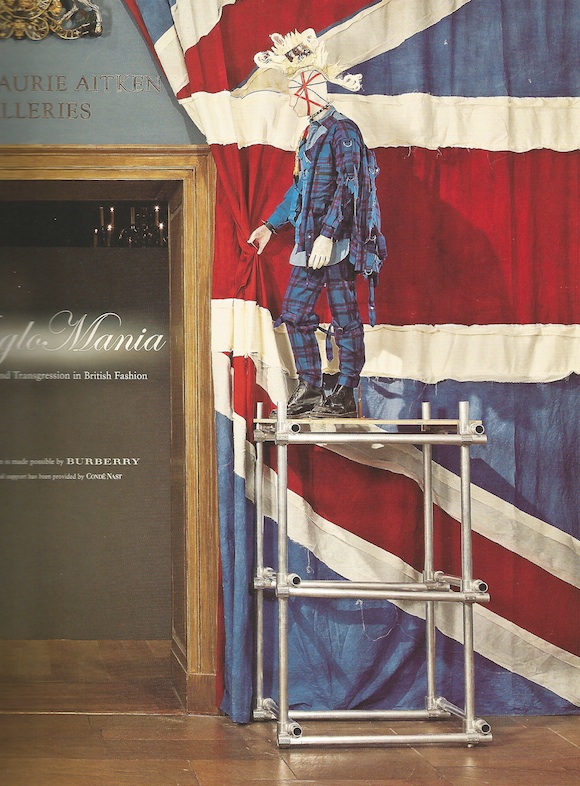

By taking these actions, the Met is communicating that it can no longer provide absolute guarantees for clothes for which it paid top dollar and featured prominently in such Gala Ball-led extravaganzas as 2006’s Anglomania: Tradition & Transgression In British Fashion and last year’s Punk: Chaos To Couture.

//Photography of the Parachute Shirt on the left (seen here paired with a John Galliano creation for the press preview of the Met’s 2013 exhibition Punk: Chaos To Couture) has been removed from the Met website with the archival status officially downgraded to “Attributed to” McLaren & Westwood//

The majority of the Met’s punk acquisitions occurred in 2006, when it bought nearly 50 garments purporting to be McLaren & Westwood originals, using funds from three official sources: The Richard Martin Bequest (named for the late historian and CI curator), The Friends Of The Costume Institute Gifts and NAMSB Foundation Inc.

At this time, before a series of alarms over counterfeiting rocked the market for these designs, each would have fetched upwards of £1,000 – £5,000. Many of the problematic items of clothing at the Met stem from this period.

In May 2013 I visited the museum and reviewed the collection of 1972-1980 designs by McLaren & Westwood. In the report I delivered to the Met last summer, I expressed the opinion – and outlined in detail the reasons why I believe – that an embarrassingly large number of the clothes are indeed fake. Several more are at the very least questionable, and at the time of my visit many were misdated and misattributed.

During the review I encountered easily fixed but nevertheless egregious mistakes: the archival listings credited each of the designs solely to Westwood, for example, and inexplicably it is her name alone which remains on the title page for each (the museum does not credit Dolce without Gabbana for example).

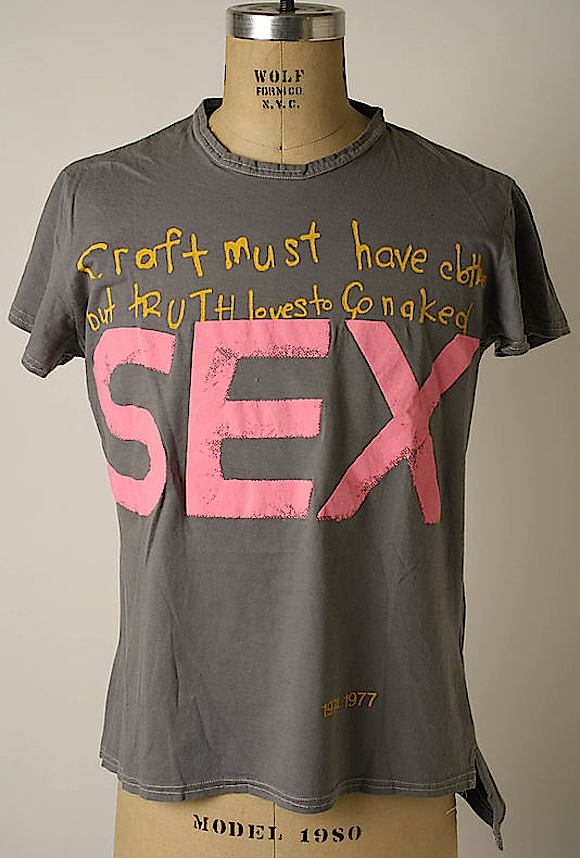

There were many howlers. A few examples: Sex and Seditionaries logo t-shirts featuring Westwood’s Red Label (launched 1993) were mistakenly allocated to the partnership in the 70s; a version of Westwood’s t-shirt rant about Derek Jarman’s film Jubilee was dated 1976 (two years before the film was made); and Too Fast To Live To Young To Die clothes were attributed to the late 70s (the store’s incarnation was 1972-74).

//One of two Vivienne Westwood Red label 90s shirts until recently claimed by the Met to be original McLaren/Westwood 70s designs//

//The bondage trousers on the mannequin in the foreground of this tableau from the Met’s 2006 Anglomania exhibition were designated in the show and catalogue to “Seditionaries, McLaren/Westwood, 1977-78”. They are – as the label inside clearly indicates – Westwood Red label (which was launched in 1993). Meanwhile the photography for the You’re Gonna Wake Up t-shirt on the mannequin lying bottom right has been removed from the Met website and the listing is among those which now has the caveat “attributed to” in the description//

Some were dead giveaways: for example an unusual leather jacket with a Worlds End Born In England label was dated 1979, a year before the label was even launched, a strange black version of the 1978 Gimp Mask/Union Jack t-shirt was (and continues to be) dated 1974, and a pair of Westwood Red-labelled black bondage trousers were mistakenly featured as originals, dated 1977-78 in the Met’s 2006 show Anglomania.

As of this week, these trousers are now dated to 1976 (17 years before the label which they bear was created) in the collection and on the Met website. Meanwhile photography of a Seditionaries-labelled Parachute Shirt which features poorly conceived elements migrated from the Anarchy Shirt design and a patch of Josef Stalin (this was never applied by McLaren & Westwood to their work**) has also been pulled from the website though once again the item remains in the collection.

In another example I pointed out that a Vive Le Rock!/Punk Rock Disco t-shirt purporting to have been sold at Seditionaries bore a tag for the US manufacturer Hanes. I have since established that this shirt was one of a batch produced in London in 1984, four years after Seditionaries closed and McLaren & Westwood ceased producing the design.

Last autumn and winter others with knowledge of the field were invited to give their views; I was informed these largely coincided with mine. In March this year the museum marked two tartan bondage suits with Seditionaries labels – one of which also featured prominently in the Anglomania show and catalogue – for de-accession.

Six months later, as of today (September 2), these bondage suits remain in the collection.

//Jacket of bondage suit marked for de-accession by the Met in March 2014. Photography on website on September 1, 2014 with listing designation changed to “Attributed to”//

//Jacket of bondage suit marked for de-accession by the Met in March 2014. Photography on website on September 1, 2014 with listing designation changed to “Attributed to”//

//The bondage suit marked for de-accession featured in the frontispiece of the catalogue for the Met’s 2006 show Anglomania//

In March 38 garments were classified “pending further review” with the photographs removed from 31 of the listings on the Met website.

Among these are such dubious items as the t-shirt titled “And Sloppy” (see first image of this post) about which I wrote in my report:

“This is not in my opinion a design by McLaren & Westwood. The lack of skill in execution, weak placement, poor juxtaposition and banal content reveal a lesser hand. A smaller version of the pink playing card was used as a repeat print on another design. This appears to be a scan of that blown up and flouro-ed. The text comes from a 1977 article by Charles Shaar Murray in the New Musical Express; such clumsy appropriations are not aligned to the content choices made by McLaren and Westwood. It appears to be an attempt by migrating a familiar element from another work to create a one-off or rarity and thus counter the lack of documentary and anecdotal evidence as to its existence.”

In April I wrote to Costume Institute curator Andrew Bolton asking why such items were still featured on the Met website and remained in the collection. I also asked why the tartan bondage suits had not been de-accessioned but continued to be listed with full photography. He responded in May that the decision-making process continued and that the duration of the assessment could not be predicted.

Two weeks ago, I asked again why the Met had not taken steps to de-toxify the collection, since items such as “And Sloppy” and the Hanes shirt remain listed along with the two tartan bondage suits selected for de-accession. I have received confirmation of receipt of my inquiries but no responses to my questions.

It is evident that behind-the-scenes activity has been taking place of late, with the museum hastily altering the listings and inserting “Attributed to…” for the 31 items, which include “And Sloppy”, the Hanes Vive Le Rock! and the tartan bondage suits along with the problematic Parachute Shirt, the Jarman t-shirt, a mohair sweater and two pairs of Seditionaries boots.

But this solution raises more questions than it answers:

• By who are these clothes now attributed to McLaren & Westwood?

• It is reasonable to infer from the insertion of “Attributed to” that there is now a margin of doubt at the Met that these were made by McLaren & Westwood or under their direction; if they were made by others, without McLaren & Westwood’s involvement, how does the museum explain the presence of original-looking labels?

• The presence of this labelling on the clothing further magnifies the difficulties for the Met; either these are original garments designed by McLaren & Westwood or they are not. Which is it, since “Attributed to” is apparently meaningless in this context?

• What of the vendors who sold these as original, authentic items; since they are no longer accepted as such, will the vendors be required to return the payments which they received?

• Since this denotes the museum’s acceptance that 30-odd items of clothing are seriously open to question, why has it opted for this fudge rather than de-accessioning them all?

I have written to the museum again seeking answers and anticipate a response once New York wakes up after the Labor Day holiday.

It is to be hoped that the Met’s move presages a clean-sheet stance to this material with progress to de-accessioning of toxic garments. In this way the museum may regain credibility after what appears to be a series of potentially costly failures in collecting materials for arguably the world’s greatest fashion archive.

* According to the Met’s collection principles “the Museum may deaccession but generally does not dispose of works determined to be forgeries. Curatorial departments generally retain these works for study purposes or seek the Director’s permission to destroy the objects, unless it can be determined that disposal can be accomplished in a responsible manner without confusion to a possible buyer. Works incorrectly attributed or dated may be de-accessioned, provided that the new information or attribution is provided”.

** In a New Yorker piece decades later, McLaren wrote about the creation of punk fashions and mistakenly mentioned Stalin instead of Karl Marx, whose image appeared on patches on the partnership’s Anarchy Shirt. He regretted this error when shirts bearing Stalin’s image were subsequently circulated.