Conversation: Lloyd Johnson + Ben Olins on Brighton Rock

Place: Golden Square, London W1.

Time: 1pm

Coffee: Nordic Bakery Soho

Lloyd Johnson, Ben Olins and I met on a sunny Saturday for a chat about Rowan Joffe’s recently-released film Brighton Rock. The transposition of the storyline to 1964 has resulted in marketing which leans heavily on the backdrop of the Mods vs Rockers “riots” in British coastal resorts that year.

Pretty Green and Merc are among promotional partners; there lingers the distinct impression of an attempt to reach out to cinemagoers by creating a British version of the Mad Men buzz.

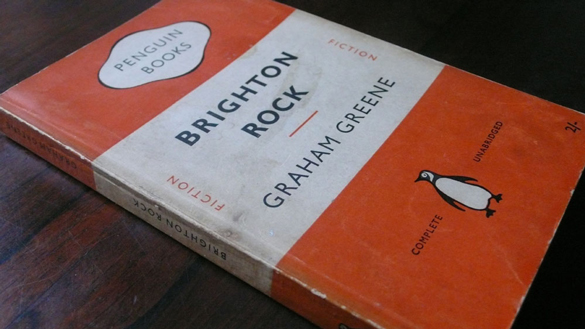

In fact the mod content is a gloss overlaying this stodgy interpretation of the 1947 film classic rather than Grahame Greene’s 1939 novel (despite claims to the contrary; Joffe even chose the first film’s climactic cop-out, against the author’s wish for an unremittingly bleak ending).

An original modernist raised in neighbouring Hastings, Lloyd has considerable first-hand knowledge of the subject and worked on the film which is a primary visual influence: Quadrophenia.

Ben’s fascination for the period is manifested in such activities as the club-night The Fabulous Cellar and certain aspects of his media company Herb Lester Associates.

As a cradle Catholic my heart sank when I heard the word on this; one of the great literary investigations into good and evil recast as a mod rite of passage. Mod really is the mainstream option these days isn’t? So codified as to be meaningless and square beyond belief: all those “rules”, all that conformity. For that, and many other reasons, the film lived down to my low expectations.

What do you reckon?

Lloyd: It was pointless. You kept on thinking: why remake a film which is still great? I missed all the dark, scary angles and shadows of the original. Richard Attenborough’s Pinkie Brown is frightening. This guy (Sam Riley) isn’t.

That’s a result of the re-purposing of the plot, which removed a key aspect of the book and the first film: the embodiment of amorality in an adolescent boy. By taking it out of the context of the impending world war (or the post-war uncertainties which reverberate around the 1947 film even though it is set in the same timeframe) the drama is lost and the mod thing revealed for what it is: froth.

Ben: I agree. I loathed this version. I didn’t go there, but it looked like something from Vintage At Goodwood. You don’t want to be pernickety but if the decision is to shoehorn mod into the story, get it right. The clothes were all over the place – Regency guys from 66-67 next to scooter boys from four years earlier – and the extras looked too well-fed and too old.

Lloyd: I know! We were 15 to 18, tops. After that you got out, moved on. And some of those guys with shaved heads! One of the most important things at that time was our hair. The scooters were all over-embellished anyway. The wardrobe shouldn’t have allowed any of these things on film.

Ben: The research seems to have been watching Quadrophenia. Mind you the rockers looked better, but I doubt any girls had giant rockabilly quiffs. They’re more appropriate to the early 80s or the burlesque scene now. I half expected to see tattoo sleeves on those girls when badly dyed, bleached blonde hair would have been more accurate.

Lloyd: Rockers are easy to get right, aren’t they? It’s an unchanging look while mod is much trickier. It changed almost weekly at that time so you have to be on your toes – and know your stuff – to get it right.

Since you mention hair, what about Cubitt (played by Craig Parkinson as an unreconstructed Ted)? For me he was pretty unconvincing, and not just because of the performance. The drape jacket was OK but the much-on-display selvedge jeans and George Cox creepers – wrong. I remember the jeans of the throwback Teds of the early to mid-60s; thin denim, Empire-made.A pair of those with thick-soled or winkle-picker Densons would have looked fab AND authentic. Again, inadequate research undercut the film’s ambitions.

Ben: With those sideburns he looked like Russ Abbot or the guy out of The Flying Pickets! An 80s idea of Ted.

Lloyd: And anyway, those older guys would wear understated winkle-pickers and box jackets and shirts in shadow-stripe fabrics.

Obviously there is the historical disconnect of a razor gang – 30s/40s/early50s – not only active but almost owning the town in the 60s, but the look of the opening section (before the mod/rocker motif takes off) was appropriate, I thought. Guys in shapeless suits, braces over grubby shirts in mealy-mouthed pubs. Sean Wilson as Hale looked spot-on and filled the role. I was five in 1964 and clearly remember people who looked like that and places with the atmosphere this conveyed. It felt right. As soon as the preposterous “transformative” moment occurred (when Pinkie dons a three button Italian blue suit and fishtail parka and takes off on his scooter at the head of a vast phalanx of mods) I was done.

Ben: That’s because it didn’t make narrative sense. He’d shown no previous interest in mod. The other transformative moment (when the dowdy Rose, played by Andrea Riseborough emerges from a Brighton boutique as a decked-out dollybird) was more plausible but again the clothes were wrong. And were there such über-Swinging London stores outside of London at the time?

Lloyd: There were. In Hastings we had one and there was a branch of Biba in Brighton pretty soon after the London store opened (in 1964), so I didn’t have a problem with that.

What about the sets? The pubs and pier were suitably seedy, but too many times the places jarred: the foyer of the hotel occupied by Colleoni the gangster (Andy Serkis) was all Courreges/Gernreich Futurismo, like something out of Polly Magoo…

Ben: The ball chair in his suite looked so placed.

Lloyd: And out of place.

Ben: I think one of the production team thought: “If I can get this into a scene I can buy it afterwards at a good price.”

…and the brutalist block of flats where Rose lived with her father was absurd. It would have been brand spanking new, not dilapidated and boarded with sheets of corrugated iron. That was out of a 70s documentary on the failure of 60s architecture.

Ben: There was The Regency, which everyone uses, and exactly the same shot of doorbells in Mornington Crescent which appeared in An Education.

Lloyd: That was wonderful film; the period detail was much better realised.

That’s because An Education wasn’t hung up on style to sell the film.

Lloyd: Mind you I thought Andy Serkis was great, as was Helen Mirren. She looked fantastic.

Ben: But there was too much trumpeting of her sexiness. It was very heavy-handed. The scene where Mirren is brushing up the broken glass after the mods attack her tea-shop is ridiculous: on all fours with her cleavage showing and her arse in the air.

And the scene towards the very end where she saucily tells John Hurt (playing bookie Phil Corkery) to get a room for them both at the hotel was laugh-out-loud. OK, we get it. Helen Mirren is a sexy senior citizen, you know?

So, come on, what did you like about it? The direction is solid and, as I’ve said, the early scenes gave me the feel of post-austerity England. While I found Riley too bland to play a soul in torment (as in Control) and Serkis hammy (see also Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll), the consistency delivered by certain cast members – particularly Hurt, Mirren, Riseborough, Wilson and Philip Davis – maintained the momentum until the plot was torpedoed by mod.

Lloyd: Along with Helen Mirren I think Rose (Riseborough) was really good. I also liked the opening sequence; the swirling, black sea and the credits beamed from the lighthouse. But I couldn’t watch it again.

Ben: Seriously, that would be torture. Apart from everything else we’ve mentioned, it’s too long, with two endings too many by my count. As somebody obsessed with this period it was a great disappointment.